Inception

Christopher Nolan’s Inception shares a lot of similarities with Tarsem Singh’s The Cell*. It’s a highly ambitious story dealing with entering people’s minds and has grand and stylized visuals, and a harrumphing, doom-impending score by Hans Zimmer that could easily be confused for Howard Shore’s work (Along with The Cell, Shore writes music for most of David Cronenberg’s films). Inception even has an endlessly convoluted structure, which requires the characters to stand around explaining the complexities of the plot every five minutes.

Christopher Nolan’s Inception shares a lot of similarities with Tarsem Singh’s The Cell*. It’s a highly ambitious story dealing with entering people’s minds and has grand and stylized visuals, and a harrumphing, doom-impending score by Hans Zimmer that could easily be confused for Howard Shore’s work (Along with The Cell, Shore writes music for most of David Cronenberg’s films). Inception even has an endlessly convoluted structure, which requires the characters to stand around explaining the complexities of the plot every five minutes.

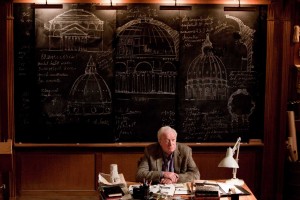

Inception also reaches the point where some very good actors (Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Ellen Page, Ken Watanabe, Michael Caine) are stranded without anything to play and are simply required to provide exposition. A wealth of character actors are sunk by the overly expository nature of the script, which is what ruined the pacing and tone of Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island. That film, like Inception, starred Leonardo DiCaprio as an arrogant and in-over-his-head “expert” who is haunted by his dead wife and must admit to and deal with his emotional deficiencies before he’s allowed to move on.

But, unlike Scorsese and Singh, Nolan is not in genre mode for his film. And Inception manages something that none of the other equally clever but cold films that Nolan has directed have achieved: We care about what’s going on.

But, unlike Scorsese and Singh, Nolan is not in genre mode for his film. And Inception manages something that none of the other equally clever but cold films that Nolan has directed have achieved: We care about what’s going on.

Unlike his Memento — which is a very intricate and intelligent film that is purely mechanical; or his Batman films, which are overstuffed if interesting to look at — Inception is directly involving on a personal level.

Sure, Inception features Nolan’s need to create new worlds for us to be blown away by. But, like his very successful remake of Insomnia, the disorientation isn’t only ours.

Sure, Inception features Nolan’s need to create new worlds for us to be blown away by. But, like his very successful remake of Insomnia, the disorientation isn’t only ours.

Yes, Inception’s plot is nothing more than a MacGuffin. The fate of the world’s energy supply is supposedly resting on businessman Watanabe’s ability to convince DiCaprio and his team to implant an idea in an unsuspecting party’s mind.

And all that takes a backseat to shootouts, ski chases a la James Bond and show-offy CGI.

And all that takes a backseat to shootouts, ski chases a la James Bond and show-offy CGI.

The difference between Inception and Nolan’s other films is that the complexities are clear and what you can ignore is saved by the fact that Watanabe’s accent is so thick that he frequently can’t be understood. Nolan plays fair with the rules — we get that DiCaprio and friends can manipulate people’s minds from inside. But the small details — like the ever-angry projections (represented as nosy strangers on the street with a short fuse), or the various time differences as they enter different levels — are always well thought out and coherent.

Like Tarsem Singh, Nolan is a master at establishing a new setting**. So, as he goes from a Japanese home — where everyone looks as though they’ve been shot with spray-tan filter — to a snowbound military bunker designed to look like a Halo 2 level, there’s none of the feeling that occurs with the globetrotting Bourne films of being that we’re someplace new because there was no way out of a scene. And they had the budget to go to Italy. So why not?

Like Tarsem Singh, Nolan is a master at establishing a new setting**. So, as he goes from a Japanese home — where everyone looks as though they’ve been shot with spray-tan filter — to a snowbound military bunker designed to look like a Halo 2 level, there’s none of the feeling that occurs with the globetrotting Bourne films of being that we’re someplace new because there was no way out of a scene. And they had the budget to go to Italy. So why not?

Instead, Nolan literalizes the elements of the brain (your wife can nag you in your subconscious). That means the locations are a necessity. And they’re so visually different: a van falling off a bridge; Gordon-Levitt fighting off intruders in a golden-hued hotel hallway that is unpredictably rotating (the most astonishing fight scene in years); and the aforementioned snowed-in bunker/bank vault. It makes the distinctions always clear as to where we are.

By doing this, Nolan does something you wouldn’t think possible for a film this complex***. He has us transfixed with the characters on each level of the mind. So he barely needs to crosscut (as opposed to requiring a “meanwhile…”). And the suspense is heightened threefold.

By doing this, Nolan does something you wouldn’t think possible for a film this complex***. He has us transfixed with the characters on each level of the mind. So he barely needs to crosscut (as opposed to requiring a “meanwhile…”). And the suspense is heightened threefold.

That he manages to maintain this balance for about 30 minutes of screen time is an extraordinary achievement; enough to overcome the niggling problems (What exactly is Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s role at the company? Is he like a film producer, in which the specifics defy description, but the overall leadership feeling is the important part?) Plus he overcomes the occasional low-tech Ouija Board**** feel of the operation.

That Nolan can get away with such chances is a credit to his enormous achievement. More so than Dark City, Blade Runner, The Matrix, and The Cell — four Warner/New Line films that Warner Brothers’ Inception will no doubt be compared to — Dark City was amazing to look at, but the characters deliberately had no core or essence. The Matrix was 100 minutes of clichéd gobbledygook which seemed to have been written by college freshman dropout, followed by 40 minutes of completely enthralling effects and cinematography.

That Nolan can get away with such chances is a credit to his enormous achievement. More so than Dark City, Blade Runner, The Matrix, and The Cell — four Warner/New Line films that Warner Brothers’ Inception will no doubt be compared to — Dark City was amazing to look at, but the characters deliberately had no core or essence. The Matrix was 100 minutes of clichéd gobbledygook which seemed to have been written by college freshman dropout, followed by 40 minutes of completely enthralling effects and cinematography.

Inception has its own gobbledygook. But the entire movie — from the slow-motion explosions of meaningless objects reminiscent of Zabriskie Point to the cityscapes folding onto each other, creating a sideways world; to a tragic and believable husband and wife relationship; to a thematically satisfying ending, that depending on your point-of-view, is either hopeful or horrifying — Nolan has basically done the impossible. He’s taken $200 million and, instead of coming up with a highly generic product, he’s made a real movie.

* The best director’s commentary ever produced for a studio film, i.e. one that had plenty of marketing and money behind it, doesn’t come from the most obvious source (Kevin Smith? Terry Gilliam?), but rather Tarsem Singh as he talks about The Cell, which was his first feature film (his second film was The Fall). Singh, who made a name for himself directing R.E.M. videos, is completely honest about the movie and the studio process itself. He talks about New Line wanting to make a film with him, and he would do it, as long as he could bring his art directors, costume designers, and any other visual element possible with him.

* The best director’s commentary ever produced for a studio film, i.e. one that had plenty of marketing and money behind it, doesn’t come from the most obvious source (Kevin Smith? Terry Gilliam?), but rather Tarsem Singh as he talks about The Cell, which was his first feature film (his second film was The Fall). Singh, who made a name for himself directing R.E.M. videos, is completely honest about the movie and the studio process itself. He talks about New Line wanting to make a film with him, and he would do it, as long as he could bring his art directors, costume designers, and any other visual element possible with him.

Since the genre du jour when The Cell was made in 2000, especially for new filmmakers, was serial killers, Singh decided to “bring his stuff with him” to a serial killer thriller. Figuring that the suits would be more worried about the script and story issues, Singh was happy to concentrate on what he enjoyed most, the look of the movie. It helped that the script for The Cell, which is about a psychotherapist (played by Jennifer Lopez) who can enter a person’s mind, is coaxed by the police to help them find the location of a missing girl, known only to a comatose serial killer, is absolutely dreadful. On the commentary, Singh talks about being totally aware of the screenplay’s many weaknesses, the contrivances, the awful dialogue, and there’s a hint that he knows that Vince Vaughn (as the cop) gives a career-worst performance. But he didn’t care, and the resulting movie has one visually stunning moment after another, as close to a series of violent, living paintings as a mainstream movie can get.

The result is that the first time you see The Cell, you’re annoyed with how poorly the story elements hang together and the idiocy that escapes any time an actor opens their mouth. The second time, you learn to ignore the problems and bask in the movie’s grotesque wonder and the wonderfully bombastic score by Howard Shore.

The result is that the first time you see The Cell, you’re annoyed with how poorly the story elements hang together and the idiocy that escapes any time an actor opens their mouth. The second time, you learn to ignore the problems and bask in the movie’s grotesque wonder and the wonderfully bombastic score by Howard Shore.

** Mike Figgis’ Timecode, which was shot in one take, with intertwining stories broken up into four different panels, has a scene in which the music emotionally matches for each separate story at the same time.

*** Singh’s The Fall is almost entirely made up of striking establishing shots, and not much else.

**** Dileep Rao has a very similar role here, as a legally questionable chemist, to the one he had in Drag Me to Hell.