Do You Have Any Change For the Trending Machine? Part I: The Living Wake

There’s a reason the public, and especially those within the industry, consider Hollywood executives as the unofficial whipping boys for the evil studio system. It doesn’t only have to do with their need to justify their jobs by offering up extraneous and contradictory notes and suggestions for filmmakers to improve their products. It isn’t just because they have to please shareholders and accountants who should, theoretically, have nothing to do with the artistic process. No. These side issues are not the cause, but the effect of trying to guess in advance what the public wants — based on past success.

There’s a reason the public, and especially those within the industry, consider Hollywood executives as the unofficial whipping boys for the evil studio system. It doesn’t only have to do with their need to justify their jobs by offering up extraneous and contradictory notes and suggestions for filmmakers to improve their products. It isn’t just because they have to please shareholders and accountants who should, theoretically, have nothing to do with the artistic process. No. These side issues are not the cause, but the effect of trying to guess in advance what the public wants — based on past success.

This is a nonsense idea because, by the time the movie is finished, the next fad will have taken over and the reasons for a film’s success can‘t often be predicted. The success may have to do with current events (The China Syndrome), or whether the overpaid lead so sought after two years previous is no longer popular with the public, or maybe a snowstorm on opening weekend. The executives, who will probably be replaced by the time their movie comes out (meaning the film will get dumped by the future administration, as they won’t be given credit if the film succeeds, which is why a film as amusing and nasty as The Midnight Meat Train never had a chance), have to analyze meaningless statistics about box office grosses and throw darts at the wall to prove that their second-guessing has the appropriate amount of knowledge and authority behind it.

As a response to that idea, screenwriter William Goldman famously wrote when referring to Hollywood that “nobody knows anything.” And he was right. This assessment is made even more astute by the current economic downturn, resulting in a lot of films that had been destined to go direct-to-video after being on the shelves for several years (Repo Men, She’s Out of My League, Daybreakers) getting a theatrical release and a heavy marketing push. The ads for these films saturate TV to ensure that awareness is high before bad word-of-mouth can set in following opening weekend.

As a response to that idea, screenwriter William Goldman famously wrote when referring to Hollywood that “nobody knows anything.” And he was right. This assessment is made even more astute by the current economic downturn, resulting in a lot of films that had been destined to go direct-to-video after being on the shelves for several years (Repo Men, She’s Out of My League, Daybreakers) getting a theatrical release and a heavy marketing push. The ads for these films saturate TV to ensure that awareness is high before bad word-of-mouth can set in following opening weekend.

The studio means for these acrobatics to partially show good faith that they put in an effort, but that “such-and-such director” is to be blamed for not delivering what the audience wanted. You can see examples of this behavior during the last few months in films like the undercover/dirty/uncaring cop thriller Brooklyn’s Finest, made by Antoine Fuqua in 2008 and finished for Sundance in January 2009 — but finally released in March of 2010. The TV ad presented the most clichéd movie possible*, but it sure aired a lot. So much so that audiences responded by theoretically making the film financially successful. Of course considering the heavy advertising blitz, there’s no way that the marketing campaign didn’t exceed the film’s budget of $25 million.

Why would a studio take such a tack when it’s doomed to fail? Were they trying to negotiate some other deal with Fuqua and — by proving that his films don’t make money, — he should take a pay cut? Or was that strategy aimed at the film’s stars Don Cheadle, Richard Gere and Ethan Hawke? And who’s to know if their stars will have fallen to the point of being forgotten about? So worrying about contract negotiation now will seem foolish is a few years, when whatever movie they’re working on gets released?

Why would a studio take such a tack when it’s doomed to fail? Were they trying to negotiate some other deal with Fuqua and — by proving that his films don’t make money, — he should take a pay cut? Or was that strategy aimed at the film’s stars Don Cheadle, Richard Gere and Ethan Hawke? And who’s to know if their stars will have fallen to the point of being forgotten about? So worrying about contract negotiation now will seem foolish is a few years, when whatever movie they’re working on gets released?

The randomness of such decisions results in executives trying to put together a “sure thing” by throwing in every possible element that was popular in the past. Avatar explains why Clash of the Titans was converted to 3-D after already having been finished. Titanic explains why Pearl Harbor had such a lengthy romantic subplot to go with the action.

But what happens when an independent film tries to bank on the successes of other small films, such as the recent glut of Wes Anderson imitators — self-aware and precious films like The Brothers Bloom? Because an independent film’s success is almost always more random than a studio film’s, because you have to factor in the possibility of the distributor actually going out of business — let alone providing money for marketing — it’s pretty strange to bank on audience awareness of a minor hit in order to explain what you’re trying to do (like a niche within another niche).

But what happens when an independent film tries to bank on the successes of other small films, such as the recent glut of Wes Anderson imitators — self-aware and precious films like The Brothers Bloom? Because an independent film’s success is almost always more random than a studio film’s, because you have to factor in the possibility of the distributor actually going out of business — let alone providing money for marketing — it’s pretty strange to bank on audience awareness of a minor hit in order to explain what you’re trying to do (like a niche within another niche).

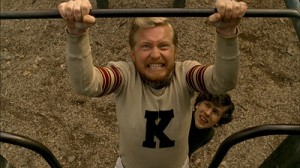

Sol Tryon’s The Living Wake was shot so long ago — in 2005, with the movie being finished in 2007 — that’s it’s almost impossible to determine its stylistic influences. With its absurdist humor — which is a little Airplane (“someday, I’ll explain it to you as a brief, but powerful monologue”); a little Monty Python (pretentious ponce sitting in the back of a rickshaw making nonsense proclamations); a little Zelig (the opening section details what a misunderstood multi-faceted genius and loner the movie’s hero, K. Roth Binew is); and a lot of Wes Anderson (like virtually every character in The Royal Tenenbaums — Binew has a series of books he’s written with wacky titles and crayon illustrations, such as The Ambitiousless Donkey).

But one influence that is most pertinent and probably less obvious to Tryon and star and co-writer Mike O’Connell is the Canadian sketch show The Kids in the Hall.

The Living Wake, which deals with Binew’s last day on Earth — as he proclaims to whomever will listen — is a 1850-1950s timewarp. Binew’s loyal rickshaw driver and biographer, played by Jesse Eisenberg, could, with very few adjustments, star Dave Foley as Binew and Kevin McDonald as the driver. What The Kids in the Hall excelled at was parodying a style and an era, without ever having a specific target**. The Kids in the Hall example that comes to mind is The Life of Cyril St. John, a “documentary” about a 1950s escape artist who gets stuck in a straightjacket and proceeds to work it into the rest of his life, including sitcoms and Chaplinesque tax problems and exile. The Living Wake is like The Life of Cyril St. John at feature length, instead of a much more palatable eight minutes.

The Living Wake, which deals with Binew’s last day on Earth — as he proclaims to whomever will listen — is a 1850-1950s timewarp. Binew’s loyal rickshaw driver and biographer, played by Jesse Eisenberg, could, with very few adjustments, star Dave Foley as Binew and Kevin McDonald as the driver. What The Kids in the Hall excelled at was parodying a style and an era, without ever having a specific target**. The Kids in the Hall example that comes to mind is The Life of Cyril St. John, a “documentary” about a 1950s escape artist who gets stuck in a straightjacket and proceeds to work it into the rest of his life, including sitcoms and Chaplinesque tax problems and exile. The Living Wake is like The Life of Cyril St. John at feature length, instead of a much more palatable eight minutes.

Apparently, The Living Wake began as a 20-page, one-man show by O’Connell — and that’s about all his concept can handle. Binew is made up to look like a fey, red-headed Martin Sheen. And for the first 20 minutes, the conception of the upper-crust Binew in a yokel town trying to complete his list of things to do before he dies (which include buying a coffin, sneaking his books into a library for future generations, and making up with his surly neighbor — played by totally out-of-place comedian, Eddie Pepitone), the movie works as self-aware silliness. Binew’s obnoxiousness is tolerable in small doses. But O’Connell (and co-writer Peter Kline) appear to run out of ideas, as the last hour is nothing but a long slog of padding. The energy flags once the initial inspiration dissipates.

For some reason, despite the constant breaking of the fourth wall, O’Connell thinks we’ll care about the twerpy Binew and find his demise moving. This is a lesson probably impugned from Wes Anderson, who mastered the mix of nonsense and vulnerability. But O’Connell then throws in a series of musical interludes, which are on-the-nose in the lyrics. They’re not nearly wacky enough to maintain the tone established in the first act. By the time we get to the Terry Gilliamesque conclusion, where Binew stages a deliberately amateurish stage show for those who showed up to his funeral, it’s clear that director Tryon is just padding to get to 90 minutes. Eisenberg, whose part was initially that of a mute, struggles to maintain his British accent, but is obviously only on screen as a straight man to Binew’s foolishness.

For some reason, despite the constant breaking of the fourth wall, O’Connell thinks we’ll care about the twerpy Binew and find his demise moving. This is a lesson probably impugned from Wes Anderson, who mastered the mix of nonsense and vulnerability. But O’Connell then throws in a series of musical interludes, which are on-the-nose in the lyrics. They’re not nearly wacky enough to maintain the tone established in the first act. By the time we get to the Terry Gilliamesque conclusion, where Binew stages a deliberately amateurish stage show for those who showed up to his funeral, it’s clear that director Tryon is just padding to get to 90 minutes. Eisenberg, whose part was initially that of a mute, struggles to maintain his British accent, but is obviously only on screen as a straight man to Binew’s foolishness.

It’s not that Binew’s pompousness is the problem; it’s that Act II and Act III have no humorous variations on whatever they think they’re making fun of. Binew then throws in deliberately vulgar sexual references, as if O’Connell was desperate to get our attention but couldn’t think of a way to do it. So he has Binew say “vagina,” even though it’s totally out of character. However, it would be fair to say that a torrent of exasperated profanity is a proper response to The Living Wake.

* And in a lot of ways accurate. Apart from one late scene where Richard Gere tries to treat the local hooker like a real girlfriend, but realizes his mistake too late, Brooklyn’s Finest is a completely predictable cop thriller. It’s derivative to the point that you might think that the whole thing is actually a parody.

* And in a lot of ways accurate. Apart from one late scene where Richard Gere tries to treat the local hooker like a real girlfriend, but realizes his mistake too late, Brooklyn’s Finest is a completely predictable cop thriller. It’s derivative to the point that you might think that the whole thing is actually a parody.

** Saturday Night Live does this on occasion, but unfortunately focuses on one element and repeats it, such as every single Fred Armisen sketch which makes fun of non-existent Spanish talk shows by acting out clichés and stereotypes.