Swimming to Cambodia

I am not now, nor have I ever been a member of the slam poetry appreciation party. The speed with which you speak has nothing to do with the profundity. I do not know how a show like Russell Simmons’ Def Poetry Jam can garner seven seasons when the rhythms of each performer, regardless of topic (though oppression often tops the list, which is odd for someone reading their own words on television) tend to be exactly the same. It’s not that the point-of-view has to be different, or the subject matter has to be lighter, but it would be nice if there were a bit of variety even within the same poem.

I am not now, nor have I ever been a member of the slam poetry appreciation party. The speed with which you speak has nothing to do with the profundity. I do not know how a show like Russell Simmons’ Def Poetry Jam can garner seven seasons when the rhythms of each performer, regardless of topic (though oppression often tops the list, which is odd for someone reading their own words on television) tend to be exactly the same. It’s not that the point-of-view has to be different, or the subject matter has to be lighter, but it would be nice if there were a bit of variety even within the same poem.

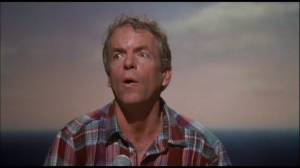

And it isn’t as if their skin color were lighter that would make any difference. When Jonathan Demme’s Swimming to Cambodia was released in 1987, the Washington Post’s critic Rita Kempley described monologist/performer/star/step-grandfather of slam poetry Spalding Gray as “a nondescript white guy who never gets out of his chair,” and that was in the middle of a very positive review. In other, less kind reviews, such as Pauline Kael’s New Yorker piece, she said that “his words come faster, his voice gets louder. He thinks like an actor; he doesn’t know that heating up his piddling stage act by an account of the Cambodian misery is about the most squalid thing anyone could do.”

And it isn’t as if their skin color were lighter that would make any difference. When Jonathan Demme’s Swimming to Cambodia was released in 1987, the Washington Post’s critic Rita Kempley described monologist/performer/star/step-grandfather of slam poetry Spalding Gray as “a nondescript white guy who never gets out of his chair,” and that was in the middle of a very positive review. In other, less kind reviews, such as Pauline Kael’s New Yorker piece, she said that “his words come faster, his voice gets louder. He thinks like an actor; he doesn’t know that heating up his piddling stage act by an account of the Cambodian misery is about the most squalid thing anyone could do.”

Now I can see Kael’s point, as it’s true that Swimming to Cambodia is a white savior story where our hero and only witness goes to a country filled with brown people, feels their misery, exploits their women, and learns valuable lessons about himself and the world, as those simplistic brown people smile and nod. But the film isn’t just about exploitation, and Gray is perfectly aware of that he’s relatively irrelevant in Thailand and on the movie he’s there to shoot, a small part in The Killing Fields. Gray was a storyteller with an ego, but also the knowledge that his ego and infidelities are what betray his idea of himself as an upstanding elite, liberal New Yorker. As his editor Suzanne Gluck said about him, “He was somebody who could experience the same boring thing as you and then spin a story from it that made you realize just how interesting it had all been.”

Now I can see Kael’s point, as it’s true that Swimming to Cambodia is a white savior story where our hero and only witness goes to a country filled with brown people, feels their misery, exploits their women, and learns valuable lessons about himself and the world, as those simplistic brown people smile and nod. But the film isn’t just about exploitation, and Gray is perfectly aware of that he’s relatively irrelevant in Thailand and on the movie he’s there to shoot, a small part in The Killing Fields. Gray was a storyteller with an ego, but also the knowledge that his ego and infidelities are what betray his idea of himself as an upstanding elite, liberal New Yorker. As his editor Suzanne Gluck said about him, “He was somebody who could experience the same boring thing as you and then spin a story from it that made you realize just how interesting it had all been.”

Certainly that’s what Demme does with the filmed version of Gray’s stage performance, mostly getting out of the way, apart from the use of Laurie Anderson’s bass violin and anxiety score. This scaling back is a perfect juxtaposition for the material, because Swimming to Cambodia is about Hollywood and white imperialist decadence and how it can suck you in. Gray describes a military man he meets on a train as “if the women in the country don’t turn him on, he misses the whole landscape.” Gray is focused on the phoniness of all of it, even the specificity of the title which refers to Gray’s need to find a “perfect moment,” so he can feel as if he’d truly experienced the country.

Certainly that’s what Demme does with the filmed version of Gray’s stage performance, mostly getting out of the way, apart from the use of Laurie Anderson’s bass violin and anxiety score. This scaling back is a perfect juxtaposition for the material, because Swimming to Cambodia is about Hollywood and white imperialist decadence and how it can suck you in. Gray describes a military man he meets on a train as “if the women in the country don’t turn him on, he misses the whole landscape.” Gray is focused on the phoniness of all of it, even the specificity of the title which refers to Gray’s need to find a “perfect moment,” so he can feel as if he’d truly experienced the country.

Part of this artificial notion of a “perfect moment” is an initiation with marijuana, which Gray claims not to have smoked in a long time, and not being particularly fond of (even if the same thing happens in his monologue about skiing, It’s a Slippery Slope), but then, Gray admits early on that not everything he says and will say is true. That approach is helpful in distracting us from the surreal horrors that he describes, how Nixon was instrumental in creating the Khmer Rouge (who were, according to Gray, thought of as hillbilly hippies) while giving us his impression of The Killing Fields director Roland Joffe as a combination of Zorro, Jesus, and Rasputin*. He doesn’t delve into the unfortunate irony of producer Uberto Pasolini, relative of Pier Paolo Pasolini, the director who was murdered for his outspoken political beliefs against the Italian government, gawking at the survivors of the Khmer Rouge like animals at the zoo. On that very trip where Pasolini appreciates the locals, Gray admits to skipping over the 15 hour trip across the third world country as “another monologue in and of itself.”

Part of this artificial notion of a “perfect moment” is an initiation with marijuana, which Gray claims not to have smoked in a long time, and not being particularly fond of (even if the same thing happens in his monologue about skiing, It’s a Slippery Slope), but then, Gray admits early on that not everything he says and will say is true. That approach is helpful in distracting us from the surreal horrors that he describes, how Nixon was instrumental in creating the Khmer Rouge (who were, according to Gray, thought of as hillbilly hippies) while giving us his impression of The Killing Fields director Roland Joffe as a combination of Zorro, Jesus, and Rasputin*. He doesn’t delve into the unfortunate irony of producer Uberto Pasolini, relative of Pier Paolo Pasolini, the director who was murdered for his outspoken political beliefs against the Italian government, gawking at the survivors of the Khmer Rouge like animals at the zoo. On that very trip where Pasolini appreciates the locals, Gray admits to skipping over the 15 hour trip across the third world country as “another monologue in and of itself.”

Unfortunately that’s where our real-life knowledge of Gray, and his eventual and sadly predictable suicide distracts us from the material that should be enveloping us. Demme’s set is very spare (which he also effectively did in Stop Making Sense), so we notice everything, such as in the first shot, just over Gray’s right shoulder, is a black string with a loop in it, very much resembling a noose. That the string turns out to be something that allows Gray to pull down a map and point out specific things to us isn’t evident for at least 20 minutes, so the suicide motif lingers with us. It isn’t Demme’s fault that he wasn’t able to anticipate an event that took place 17 years after his film was released (Gray died in 2004), but it is his fault that the occasional transitions are awkwardly handled, as if the performance had to stop and reset, instead of just being an intense 85 minute monologue. If these minor deficits cause your mind to wander, that seems fair**, because Gray is never too far from reminding you of your own self-indulgence, and that he knows how he sounds, such as when he describes his upstairs neighbor as a profanity martyr and how he’s “convinced she’s a masochist and is getting off on the language.” What better way to describe Gray and his audience as those who are language masochists? You’re not going to find that many levels of Meta in a slam poem.

Unfortunately that’s where our real-life knowledge of Gray, and his eventual and sadly predictable suicide distracts us from the material that should be enveloping us. Demme’s set is very spare (which he also effectively did in Stop Making Sense), so we notice everything, such as in the first shot, just over Gray’s right shoulder, is a black string with a loop in it, very much resembling a noose. That the string turns out to be something that allows Gray to pull down a map and point out specific things to us isn’t evident for at least 20 minutes, so the suicide motif lingers with us. It isn’t Demme’s fault that he wasn’t able to anticipate an event that took place 17 years after his film was released (Gray died in 2004), but it is his fault that the occasional transitions are awkwardly handled, as if the performance had to stop and reset, instead of just being an intense 85 minute monologue. If these minor deficits cause your mind to wander, that seems fair**, because Gray is never too far from reminding you of your own self-indulgence, and that he knows how he sounds, such as when he describes his upstairs neighbor as a profanity martyr and how he’s “convinced she’s a masochist and is getting off on the language.” What better way to describe Gray and his audience as those who are language masochists? You’re not going to find that many levels of Meta in a slam poem.

* If Zorro, Jesus, and Rasputin = Roland Joffe, what do the stunning shallowness and workmanlike projects of his recent past, such as the Saw rip-off Captivity, the nudge-nudge silliness of his MTV sexploitation show Undressed, or the finally-out-on-DVD-after-three-years-on-the-shelf coming-of-age story You and I, about two girls who meet at a T.A.T.U. concert (the two Russian girls who pretended to be chic lesbians) and fall in love, equal?

* If Zorro, Jesus, and Rasputin = Roland Joffe, what do the stunning shallowness and workmanlike projects of his recent past, such as the Saw rip-off Captivity, the nudge-nudge silliness of his MTV sexploitation show Undressed, or the finally-out-on-DVD-after-three-years-on-the-shelf coming-of-age story You and I, about two girls who meet at a T.A.T.U. concert (the two Russian girls who pretended to be chic lesbians) and fall in love, equal?

** The further knowledge that Gray’s constant infidelity and inability to commit to Renée Shafransky, who was his life and work partner for 15 years (and was instrumental in Swimming to Cambodia coming together at all), adds another layer of sadness.

** The further knowledge that Gray’s constant infidelity and inability to commit to Renée Shafransky, who was his life and work partner for 15 years (and was instrumental in Swimming to Cambodia coming together at all), adds another layer of sadness.