Bullet in the Head

A filmmaker like Larry Clark puts a viewer in a tough spot. When watching a movie like Kids, Bully, or Wassup Rockers, are we to believe that Clark has perfectly portrayed the aimlessness and idiocy of bored, wayward teenagers in search of a good time? Or is Clark just lazy himself, and he simply hasn’t bothered to fill in any details about his characters, and is solely interested in exploiting them for their nihilistic and decadent tendencies?

A filmmaker like Larry Clark puts a viewer in a tough spot. When watching a movie like Kids, Bully, or Wassup Rockers, are we to believe that Clark has perfectly portrayed the aimlessness and idiocy of bored, wayward teenagers in search of a good time? Or is Clark just lazy himself, and he simply hasn’t bothered to fill in any details about his characters, and is solely interested in exploiting them for their nihilistic and decadent tendencies?

That sort of line, where a filmmaker’s attributes are exactly the same as his faults, means that he can be seen as either brilliant or incompetent, and neither is exactly wrong. What does a viewer make of director John Woo, who was a journeyman for more than ten years making kung fu films, slapstick comedy, and low-rent horror films before hitting it big with 1986’s A Better Tomorrow. That film may look quaint and dated today, but at the time it was considered an explosive action thriller, firmly establishing Chow Yun Fat as a charismatic and dangerous anti-hero. Woo’s early motifs, slow motion gun battles, “cool” action poses, doves, churches, ridiculous melodrama, a muzak-level score, minimal development of female characters, the theme of brotherhood, rapid-fire dissolve montages, and direction of the male leads to play their characters as broad and exaggerated as possible, developed from A Better Tomorrow through Hard Boiled, eventually joined him in America for Face/Off, Broken Arrow, Hard Target, and Mission Impossible II. The latter film should have been his last, as each element is so over-the-top and gratuitous, that there was no reason for him to continue making movies, every cliché he helped create is on display, poorly shoehorned in, with an enormous budget as a problem-solver.

That sort of line, where a filmmaker’s attributes are exactly the same as his faults, means that he can be seen as either brilliant or incompetent, and neither is exactly wrong. What does a viewer make of director John Woo, who was a journeyman for more than ten years making kung fu films, slapstick comedy, and low-rent horror films before hitting it big with 1986’s A Better Tomorrow. That film may look quaint and dated today, but at the time it was considered an explosive action thriller, firmly establishing Chow Yun Fat as a charismatic and dangerous anti-hero. Woo’s early motifs, slow motion gun battles, “cool” action poses, doves, churches, ridiculous melodrama, a muzak-level score, minimal development of female characters, the theme of brotherhood, rapid-fire dissolve montages, and direction of the male leads to play their characters as broad and exaggerated as possible, developed from A Better Tomorrow through Hard Boiled, eventually joined him in America for Face/Off, Broken Arrow, Hard Target, and Mission Impossible II. The latter film should have been his last, as each element is so over-the-top and gratuitous, that there was no reason for him to continue making movies, every cliché he helped create is on display, poorly shoehorned in, with an enormous budget as a problem-solver.

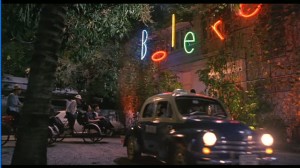

The one film that Woo put his energy into that was not accepted by the Hong Kong public during his 1986-1992 salad days (through Hard Boiled) was one he considers his favorite, Bullet in the Head. Now Bullet in the Head has all of the things that make a John Woo film a John Woo film, and whether you burst out laughing during the first ½ hour, because the editing appears haphazard and the music corny (is that a saxophone version of “Happy Birthday to You” that’s constantly used throughout the film?), is entirely subjective. Though he would ironically use music in Face/Off, an earth shattering gun battle is juxtaposed with a child listening to “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” Bullet in the Head, even when Woo repeatedly uses a poorly covered version of The Monkees’ “I’m a Believer,” never makes it clear that we’re supposed to laugh with the movie. However, by the middle section of the movie, as the characters, played by Jacky Cheung, Tony Leung, and Waise Lee, escape Hong Kong to go to Vietnam to smuggle drugs (in 1967, in the middle of the Vietnam War), the brutal violence can’t really be taken as nudge-nudge humor. Eschewing the glamorous contract killers of his previous films, Bullet in the Head has its carefree and idealistic characters repeatedly finding themselves in untenable situations, bound to corrupt them. Shooting their way out is a temporary solution which only digs them in deeper, eventually resulting in being kidnapped by the Vietcong.

The one film that Woo put his energy into that was not accepted by the Hong Kong public during his 1986-1992 salad days (through Hard Boiled) was one he considers his favorite, Bullet in the Head. Now Bullet in the Head has all of the things that make a John Woo film a John Woo film, and whether you burst out laughing during the first ½ hour, because the editing appears haphazard and the music corny (is that a saxophone version of “Happy Birthday to You” that’s constantly used throughout the film?), is entirely subjective. Though he would ironically use music in Face/Off, an earth shattering gun battle is juxtaposed with a child listening to “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” Bullet in the Head, even when Woo repeatedly uses a poorly covered version of The Monkees’ “I’m a Believer,” never makes it clear that we’re supposed to laugh with the movie. However, by the middle section of the movie, as the characters, played by Jacky Cheung, Tony Leung, and Waise Lee, escape Hong Kong to go to Vietnam to smuggle drugs (in 1967, in the middle of the Vietnam War), the brutal violence can’t really be taken as nudge-nudge humor. Eschewing the glamorous contract killers of his previous films, Bullet in the Head has its carefree and idealistic characters repeatedly finding themselves in untenable situations, bound to corrupt them. Shooting their way out is a temporary solution which only digs them in deeper, eventually resulting in being kidnapped by the Vietcong.

Now Bullet in the Head was originally supposed to be A Better Tomorrow III, a series that glamorizes criminals, before Woo had a falling out with producer Tsui Hark. Did the disagreement cause Woo to change his tone and make sure we understood how horrible violence could be? One of the mantras of the characters is, “as long as we have guns, the world is ours,” and writer/producer Patrick Leung stated in interviews that Woo’s intention was to show younger Hong Kong viewers, who had never experienced war in their country, how devastating it could be. [Shades of Kenji Fukasaku’s intention with Battle Royale.]

Now Bullet in the Head was originally supposed to be A Better Tomorrow III, a series that glamorizes criminals, before Woo had a falling out with producer Tsui Hark. Did the disagreement cause Woo to change his tone and make sure we understood how horrible violence could be? One of the mantras of the characters is, “as long as we have guns, the world is ours,” and writer/producer Patrick Leung stated in interviews that Woo’s intention was to show younger Hong Kong viewers, who had never experienced war in their country, how devastating it could be. [Shades of Kenji Fukasaku’s intention with Battle Royale.]

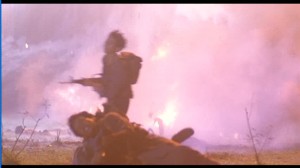

Death is a relief in the film; the baptism imagery is everywhere, especially as the characters have just expired. When Woo does his standard breaking of the 180° line (which he did in The Killer) where he disorients the audience’s sense of screen direction, it is no longer to show that two opposites are just mirror images of each other, but rather to establish that there are no good sides to be on, so following rules isn’t going to help you. The cops and the military whether they be Chinese, Vietnamese, or American (or Thai, since that’s where the Vietnam footage was shot) are faceless storm troopers in Bullet in the Head, and the lack of a charismatic center to the film, owed to the lack of Chow Yun-Fat, is an advantage, as we never feel comfortable that a character might be in control (though Simon Yam’s smoldering mercenary comes close), or live another five minutes.

Death is a relief in the film; the baptism imagery is everywhere, especially as the characters have just expired. When Woo does his standard breaking of the 180° line (which he did in The Killer) where he disorients the audience’s sense of screen direction, it is no longer to show that two opposites are just mirror images of each other, but rather to establish that there are no good sides to be on, so following rules isn’t going to help you. The cops and the military whether they be Chinese, Vietnamese, or American (or Thai, since that’s where the Vietnam footage was shot) are faceless storm troopers in Bullet in the Head, and the lack of a charismatic center to the film, owed to the lack of Chow Yun-Fat, is an advantage, as we never feel comfortable that a character might be in control (though Simon Yam’s smoldering mercenary comes close), or live another five minutes.

The fact that Leung, Cheung, and Lee stumble into the Vietnam War, observing the chaos that the locals have to deal with but without it quite seeming real to them, makes us equally uncomfortable. They’re ignorant of the war and their rewards and punishment are at the expense of those legitimately fighting for their lives, not engaging in childish versions of criminal activity. Woo doesn’t fall back on his crutch of doves and Churches, there’s no beauty in Bullet in the Head, and for once in his films, the violence isn’t pretty. Which sounds about right.

The fact that Leung, Cheung, and Lee stumble into the Vietnam War, observing the chaos that the locals have to deal with but without it quite seeming real to them, makes us equally uncomfortable. They’re ignorant of the war and their rewards and punishment are at the expense of those legitimately fighting for their lives, not engaging in childish versions of criminal activity. Woo doesn’t fall back on his crutch of doves and Churches, there’s no beauty in Bullet in the Head, and for once in his films, the violence isn’t pretty. Which sounds about right.

A note on the conclusion of Bullet in the Head: Woo’s original intention was to make the film a 3 hour epic, but the studio insisted on getting in as many showings per day as possible, and ordered him to cut it to around 2 hours. This had no positive effect on the box office, as the movie was one of the most expensive failures in Hong Kong history, closing in two weeks, because it supposedly depressed the Chinese New Year audience looking for joy and uplift.

A note on the conclusion of Bullet in the Head: Woo’s original intention was to make the film a 3 hour epic, but the studio insisted on getting in as many showings per day as possible, and ordered him to cut it to around 2 hours. This had no positive effect on the box office, as the movie was one of the most expensive failures in Hong Kong history, closing in two weeks, because it supposedly depressed the Chinese New Year audience looking for joy and uplift.

There are many cuts available around the world, and depending on who you talk to, the 130 minute theatrical version that ends with a totally incongruous and elaborate car chase is relatively close to what Woo wanted. Or, Woo preferred the 135 minute version, which includes snippets of extra war footage and the famous “piss drinking” scene. Or maybe Woo liked the 120 minute version, which eliminates the car chase ending for a much more abrupt yet thematically appropriate ending. Ideally, Woo would chime in, but it appears to me that the “best” version, which doesn’t exist, would include both the “piss drinking” scene and the abrupt ending. That composite version, with subtitles I re-wrote, is what I used for this review.

There are many cuts available around the world, and depending on who you talk to, the 130 minute theatrical version that ends with a totally incongruous and elaborate car chase is relatively close to what Woo wanted. Or, Woo preferred the 135 minute version, which includes snippets of extra war footage and the famous “piss drinking” scene. Or maybe Woo liked the 120 minute version, which eliminates the car chase ending for a much more abrupt yet thematically appropriate ending. Ideally, Woo would chime in, but it appears to me that the “best” version, which doesn’t exist, would include both the “piss drinking” scene and the abrupt ending. That composite version, with subtitles I re-wrote, is what I used for this review.

Malik Gantt says:

January 17th, 2017

7:51 pm

do you still have this version available or do you where i can get a copy ? i cant find it anywhere and youtube used to have the piss drinking scene and the uncut version.