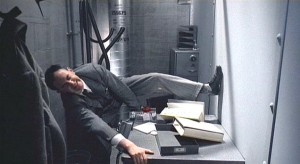

Brazil

Terry Gilliam has always claimed that studios dump or meddle with his movies because they don’t know how to sell them. I hadn’t seen Brazil in its entirety since my freshman year of college, I chalked up the hour I watched as a senior being bored and distracted as simply not being in the mood.

Terry Gilliam has always claimed that studios dump or meddle with his movies because they don’t know how to sell them. I hadn’t seen Brazil in its entirety since my freshman year of college, I chalked up the hour I watched as a senior being bored and distracted as simply not being in the mood.

Recently, I saw the director’s cut on a big screen, though I was rather confused that the opening credit scene was missing, as I was used to the cloud sequence which, by having the 1930’s version of the song Brazil sung with lyrics, sets up the constant reprisals throughout the movie as well as the cast always humming it. The deletion of that changes the tone considerably, it is no longer as if the song is running through their minds, instead they’re actually just crazy and Gilliam is being unnecessarily self-reflexive. This also removes what I always saw as the Chinatown-esque theme of the movie, that despite how awful the world they live in is now, there’s always some mysterious past or future that could be an improvement, an escape. The credits also give meaning to the endless dream sequences that litter the movie, they are how Sam sees Brazil.

Without the credits, the movie and Gilliam reveal themselves completely, a disorganized mess of jokey half-ideas with no concept of story, structure, tone, character, or the ability to establish any consistency at all, except the faceless corporate government. In the pamphlet handed out before the film, there was an interview with Gilliam who listed all the different title ideas Universal offered him, some 30 or so, almost all silly (“This Escalator Doesn’t Stop At Your Station,” “Can’t Anybody Here Play the Cymbals?,” “Fold, Spindle, Mutilate,” “Nude Descending Bathroom Scale”), all hideous, but somehow appropriate to the best parts of his film. Brazil only has meaning because of the use of the theme, giving insight into Sam’s character. Since the entire film devolves into the same joke after about an hour, he should have just called it, “Oh, isn’t it shitty.” With the film the way Gilliam wanted it, Pryce has nothing to play, a completely empty shell, and he and his love interest (with whom he does not share a scene with until 90 minutes into the movie) have no chemistry at all and no explanation as to why she’d be interested in him or what her purpose is. The terrorism subplot goes nowhere, we don’t know who they are or what they are rebelling against (if indeed it is just too much paperwork), since it is revealed the De Niro rescue is only a dream. So despite the fact that the movie, just as with The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, is supposed to represent Gilliam’s symbolic fight against the movie studios for forcing him to compromise his vision, the constant, random, meaningless, well photographed explosions are exactly the sort of thing the studio would want from one of their expensive films.

Without the credits, the movie and Gilliam reveal themselves completely, a disorganized mess of jokey half-ideas with no concept of story, structure, tone, character, or the ability to establish any consistency at all, except the faceless corporate government. In the pamphlet handed out before the film, there was an interview with Gilliam who listed all the different title ideas Universal offered him, some 30 or so, almost all silly (“This Escalator Doesn’t Stop At Your Station,” “Can’t Anybody Here Play the Cymbals?,” “Fold, Spindle, Mutilate,” “Nude Descending Bathroom Scale”), all hideous, but somehow appropriate to the best parts of his film. Brazil only has meaning because of the use of the theme, giving insight into Sam’s character. Since the entire film devolves into the same joke after about an hour, he should have just called it, “Oh, isn’t it shitty.” With the film the way Gilliam wanted it, Pryce has nothing to play, a completely empty shell, and he and his love interest (with whom he does not share a scene with until 90 minutes into the movie) have no chemistry at all and no explanation as to why she’d be interested in him or what her purpose is. The terrorism subplot goes nowhere, we don’t know who they are or what they are rebelling against (if indeed it is just too much paperwork), since it is revealed the De Niro rescue is only a dream. So despite the fact that the movie, just as with The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, is supposed to represent Gilliam’s symbolic fight against the movie studios for forcing him to compromise his vision, the constant, random, meaningless, well photographed explosions are exactly the sort of thing the studio would want from one of their expensive films.

It is ironic that Gilliam’s two biggest critical and financial hits, The Fisher King and 12 Monkeys, were ones where he was reined in the most, not allowed to branch off into the blissful incoherence he prefers, and forced to stay within the notion of dark, moralistic whimsy. In Brazil, the tone is constantly changing, even adopting noir for a 40 minute section near the middle, though nothing comes of it. The humor, while at times very funny, is overshadowed by how dour everything is, but it isn’t a caustic, sly jokiness, just a rib nudging horribleness that was perfected in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Therein lies the difference however, Python knew to quit at 90 minutes, but Gilliam, without any guidance, just hammers you for 142 minutes, without any real escalation or building, just sets popping out at you like a naive version of 3-D. It’s like an entire movie made entirely of asides, but nothing in the center. Think about what sticks with you after the movie is over, probably the same things that do in Blade Runner, the impeccable technical material, camera, sets, etc., pretty much everything that would make an amazing making of picture book, especially if Gilliam wrote, glib, silly descriptions. It’s once the images start moving that it gets him in trouble.

I’m not saying I agree with what Sid Sheinberg and Universal did with the film in terms of their producer’s cut, the one that ended up on the third disc of the Criterion set, but I agree with why they did it. The movie is unreleasable, hard to enjoy in more than 5 minute bursts, and constantly making you confused as to how the same director managed the wondrous [and coherent] Time Bandits, a few years earlier. Like the TV counterparts, Andy Richter Controls the Universe and The Tick (live action) it should be a silly movie for smart people, equal parts absurd and satirical, but Gilliam never finishes his thoughts. What Sheinberg did was try to bring out the elements of the story which can be tied together, the love story, the corporate war, everything else is just visual masturbation for Gilliam. He doesn’t even care enough for the female lead to give her an on-screen death, her disappearance is simply explained as “oh, yeah, and your lady is dead,” as if he didn’t care enough to shoot the footage. There’s no other explanation, as he shot everything else.

I’m not saying I agree with what Sid Sheinberg and Universal did with the film in terms of their producer’s cut, the one that ended up on the third disc of the Criterion set, but I agree with why they did it. The movie is unreleasable, hard to enjoy in more than 5 minute bursts, and constantly making you confused as to how the same director managed the wondrous [and coherent] Time Bandits, a few years earlier. Like the TV counterparts, Andy Richter Controls the Universe and The Tick (live action) it should be a silly movie for smart people, equal parts absurd and satirical, but Gilliam never finishes his thoughts. What Sheinberg did was try to bring out the elements of the story which can be tied together, the love story, the corporate war, everything else is just visual masturbation for Gilliam. He doesn’t even care enough for the female lead to give her an on-screen death, her disappearance is simply explained as “oh, yeah, and your lady is dead,” as if he didn’t care enough to shoot the footage. There’s no other explanation, as he shot everything else.

I used to enjoy that the movie was an incoherent mess of ideas, an endless distraction of visual flash, but perhaps those are the feelings of an idealistic 17-year-old, the same way one would fall for the simplistic rebelliousness of A Clockwork Orange. It seems likely that as one ages, it becomes a requirement to care about what’s going on in front of you, not just that it looks cool.