F For Fake

Here’s the idea behind “A Canadian, an American, a Lawyer, and an Elitist”: Rhett’s favorite movie is Meatballs 4, Shawn has an unhealthy fixation on Resident Evil, Richard scoffs at anything that isn’t pretentious and hoity toity, and Adam is a prick who hates everything. We all watch far too many movies, and spend our time analyzing them. So we each watch the same movie, write our analysis of them, and then go to a chat room to discuss it, unaware of what the others have written. A warning: if you haven’t seen the film we are discussing, it may not be best to read this article, because it is spoiler heavy.

Here’s the idea behind “A Canadian, an American, a Lawyer, and an Elitist”: Rhett’s favorite movie is Meatballs 4, Shawn has an unhealthy fixation on Resident Evil, Richard scoffs at anything that isn’t pretentious and hoity toity, and Adam is a prick who hates everything. We all watch far too many movies, and spend our time analyzing them. So we each watch the same movie, write our analysis of them, and then go to a chat room to discuss it, unaware of what the others have written. A warning: if you haven’t seen the film we are discussing, it may not be best to read this article, because it is spoiler heavy.

As is the case with most of the Elitist articles, this was written in 2005, so please keep that in mind when reading it. Lasse Hallström’s The Hoax was released in 2006, with Richard Gere playing Clifford Irving, and while financially unsuccessful, it did re-energize interest in Irving’s career which might affect how a new viewer might respond to F For Fake. However, as someone who saw F For Fake first, I thought The Hoax was an almost completely redundant film.

Analysis by a Canadian: Rhett Miller

Analysis by a Canadian: Rhett Miller

Orson Welles’ F For Fake is a mockumentary before such a thing ever existed. Always a pioneer, and never one to dwell on past success, Welles has been arguably cinema’s greatest innovator. The full sets, deep focus photography and mobile camera were all grand innovations in Citizen Kane, and his virtuoso opening shot from Touch of Evil still really has yet to be bested. The artistic successes of both Citizen Kane and Touch of Evil were made possible in part by lavish Hollywood money that gave Welles the ability to experiment, just as a painter would experiment on an unlimited canvas. But Welles, the paradox that he is, triumphed greatest when he was given the least, when he had to fight with his heart and soul to get his films made, rather than have it optioned by an investor such as Hollywood.

When Welles found himself outside of the Hollywood system, without their lavish money treatment, he was forced to focus on the storytelling brilliance that brought him to stardom in the first place, namely with War of the Worlds. There were no ceilings in War of the Worlds, but instead the film triumphed on its ability to blur the lines between fiction and reality, as Welles cut between faux programming with equally faux news reports. It put on a whole nation, and it was done with a storytelling brilliance that has rarely been equaled. His F For Fake is a return to such brilliance, albeit it on a much smaller scale. It tells the story of the world of art forgery, with peppered bits by Welles on both his career and the career of others. Welles begins the film with a bit of magic trickery, and ends the film with the art of film trickery. He deconstructs the documentary, and all its truthful, objective connotations, in order to further his thesis set forth in War of the Worlds: the masses can be fooled, no matter how smart they suppose themselves to be.

Welles’ fascination for the documentary extends not only to War of the Worlds, but also the best part of Citizen Kane. No, the viewable ceilings were not the greatest element of The Greatest Film Ever Made, instead it was Welles panache for combining different media and storytelling forms for presenting Kane with one of the most thorough characterizations in all of cinema. His life was recalled from bits of newsreel footage, recollections by acquaintances, narration, reenacted footage in the present and other such storytelling methods. In the way Kane’s life was presented, Welles made it apparent that the same story could be told by different media or approaches, and still generate radically different impressions of the same subject. F For Fake sticks to documentary, but like Kane, it demonstrates a filmmaker not afraid to combine aspects of the real and the fake in demonstrating the various methods of storytelling. Welles does such a good job at immersing the viewer into the real lives of fraud painter Elmyr de Hory and fraud writer Clifford Irving, what when he springs a fraud story of a real Pablo Picasso, the audience doesn’t see it coming.

Welles’ fascination for the documentary extends not only to War of the Worlds, but also the best part of Citizen Kane. No, the viewable ceilings were not the greatest element of The Greatest Film Ever Made, instead it was Welles panache for combining different media and storytelling forms for presenting Kane with one of the most thorough characterizations in all of cinema. His life was recalled from bits of newsreel footage, recollections by acquaintances, narration, reenacted footage in the present and other such storytelling methods. In the way Kane’s life was presented, Welles made it apparent that the same story could be told by different media or approaches, and still generate radically different impressions of the same subject. F For Fake sticks to documentary, but like Kane, it demonstrates a filmmaker not afraid to combine aspects of the real and the fake in demonstrating the various methods of storytelling. Welles does such a good job at immersing the viewer into the real lives of fraud painter Elmyr de Hory and fraud writer Clifford Irving, what when he springs a fraud story of a real Pablo Picasso, the audience doesn’t see it coming.

They should though, since Welles states right from the start that only the first hour of his piece will be unabashed truth. Like any great musician, he places all the evidence in front of the viewer’s eye, and goes on to make them forget all the evidence they’ve seen by focusing on a distraction. Welles lays out all his intentions in voice over, but uses a marvelously edited sequence with a beautiful girl to distract the viewer from the facts. The way the lovely Oja Kodar is able lastingly foil the audience is yet another testament to how easy it is to manipulate an audience with a strong visual figurehead. Like Hitler was able to mobilize millions with his propaganda, Welles is able to use the film medium the female’s to-be-looked-at-ness to whitewash the viewer. It is a wonderful bit of visual trickery, so simple, yet undeniably effective. F For Fake is a filmic manifestation of a magic show, right down to the seductively distracting female assistant.

As good as a magic trick as F For Fake is, it also works as a fine epitaph to Welles’ career. Although the focus is generally on de Hory and Irving, Welles does offer many insights into his own life. He talks of War of the Worlds and Citizen Kane, but one sense that the “Fake” of the title is not in regards to Welles’ ability to fool audiences with his Worlds hoax, but instead it alludes to how the Hollywood system spit him out as a fraud of his own making. There is a point in the film when Welles recalls a story of Picasso, when he had wrongly identified one of his own original paintings as a fake. When called upon such a seeming error of judgment, Picasso retorted with “I can paint false Picasso’s just like anybody”, and in a way that can describe Welles’ maligned Hollywood output from a similar time. The allure of the bloated dollar along with Welles’ equally bloated ego led to a Hollywood output that many would say was just Welles commercializing his artistic aspirations, making heartless pap rather than making stuff he truly wanted to make. In Hollywood he had therefore become a fake, a fraud, someone selling out on his original ideas for unearned profits. So in a way, F For Fake documents the life of fraudulent writers and painters just as it documents a self-proclaimed fraudulent filmmaker.

As good as a magic trick as F For Fake is, it also works as a fine epitaph to Welles’ career. Although the focus is generally on de Hory and Irving, Welles does offer many insights into his own life. He talks of War of the Worlds and Citizen Kane, but one sense that the “Fake” of the title is not in regards to Welles’ ability to fool audiences with his Worlds hoax, but instead it alludes to how the Hollywood system spit him out as a fraud of his own making. There is a point in the film when Welles recalls a story of Picasso, when he had wrongly identified one of his own original paintings as a fake. When called upon such a seeming error of judgment, Picasso retorted with “I can paint false Picasso’s just like anybody”, and in a way that can describe Welles’ maligned Hollywood output from a similar time. The allure of the bloated dollar along with Welles’ equally bloated ego led to a Hollywood output that many would say was just Welles commercializing his artistic aspirations, making heartless pap rather than making stuff he truly wanted to make. In Hollywood he had therefore become a fake, a fraud, someone selling out on his original ideas for unearned profits. So in a way, F For Fake documents the life of fraudulent writers and painters just as it documents a self-proclaimed fraudulent filmmaker.

F For Fake is an interesting film experiment, like more commercial ventures like The Usual Suspects would be years later. But what elevates F For Fake above such punch line films like Suspects is the heart that is seeped in the film throughout. Suspects was a film made entirely to trick the audience, but Fake is a film that tricks its audience and then tells them why, and why it all matters. More than that though, it also documents the life of one of cinema’s most celebrated figures, and in that sense the punch line isn’t nearly as important as the substance leading up to it.

Analysis by an American: Shawn McLoughlin

Analysis by an American: Shawn McLoughlin

Documentaries are often hit-or-miss, and this is usually because of the presentation. A good documentary will capture your attention, regardless of your interest in the subject. F for Fake has its “girl-watching” scene where we follow the attractive Oja Kodar as she walks along a street and we watch the people as they watch her. She is beautiful, and our attention is diverted along with the others. This diversion is the central message of the film, but it is very important that this is obvious. It is said that a good magician accomplishes his tricks by diverting their audience’s attention. Orson Welles’ F for Fake is a magic trick, and a not too subtle one at that. It diverts your standing opinion on the subject to get your attention, tell you a story, make you question what you heard, and go home questioning your original ideas. It succeeds in tricking you, in a way that most fiction can’t.

Orson is a very fun director; everything in his films is stylistically thought out and exaggerated. Everyone has seen Citizen Kane and knows the story behind it. It is based on a true person, with names and situations changed. Though it was quite obvious that everyone at the time knew who it was really about it is important that it wasn’t real. The exaggeration, and extension of the truth, added to the mystique of the film, and made what could have been a bio-picture a work of art. Similarly, as mentioned in the film, Orson himself had been considered a charlatan thanks to his convincing radio broadcast re-imagining of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds in 1938. In both cases what started as fakery, ended up as a work of art. So who better is there to make a film about art fakery then Orson Welles?

The film has no title card. Instead, there are simply two film cans labeled “about fakes” and “a film by Orson Welles” respectively. As Orson narrates most of the first two-thirds of the film, he raises more questions then a conventional documentary would. By saying the film is “about fakes” instead of “about fakers” he makes an important point. The art fakes in the film are considered masterpieces in their own right and are presented as true works of art themselves. This is a noble enough statement, and the film goes to great lengths to make the “fakers” interviewed as human as possible and, as such, decriminalize them. It never states this though, partly because it wants the audience to decide for themselves, and possibly because Orson has no room to talk. Film, after all, is a lie and actors are mere liars. Orson, a practicing magician, actor and filmmaker would possibly be the largest criminal of anyone in the industry. In fact, the ‘trick’ he pulls with the bookends of the film, by wrapping it in an un-truth, is the best evidence of his ability to manipulate.

The film has no title card. Instead, there are simply two film cans labeled “about fakes” and “a film by Orson Welles” respectively. As Orson narrates most of the first two-thirds of the film, he raises more questions then a conventional documentary would. By saying the film is “about fakes” instead of “about fakers” he makes an important point. The art fakes in the film are considered masterpieces in their own right and are presented as true works of art themselves. This is a noble enough statement, and the film goes to great lengths to make the “fakers” interviewed as human as possible and, as such, decriminalize them. It never states this though, partly because it wants the audience to decide for themselves, and possibly because Orson has no room to talk. Film, after all, is a lie and actors are mere liars. Orson, a practicing magician, actor and filmmaker would possibly be the largest criminal of anyone in the industry. In fact, the ‘trick’ he pulls with the bookends of the film, by wrapping it in an un-truth, is the best evidence of his ability to manipulate.

The “true” pieces of the film are very interesting. The interviews with Elmyr de Hory (an art faker and true artist himself) and Clifford Irving (an interviewer himself, and later co-author of a fake autobiography on Howard Hughes) are edited in such a way as to paint these subjects in a sympathetic light. Like Welles’ character Harry Lime from The Third Man, they become anti-heroes. It becomes less important whether or not what they are doing is morally right; as it is that they are able to succeed in doing it. They are admired for their ability to stick to their belief and their inability to see wrong in it. The quick cuts, particularly in this pre-MTV era, give it a very modern feel. It moves even quicker then its short length would indicate. This pacing, along with Orson’s always wonderful narration and presence, forces the viewer to understand the messages with ease. So it certainly succeeds as a documentary as well as a film.

The film forces you to ask, “What is fake?” Personally, I agree that imitation is an art form. But claiming the imitation is an original is, in my opinion, thievery. But regardless of the belief of the viewer one has to admit that the argument, and they way it is presented, is both convincing and entertaining. Ultimately, that really is all an entertaining film needs to be, and F for Fake succeeds wonderfully.

The film forces you to ask, “What is fake?” Personally, I agree that imitation is an art form. But claiming the imitation is an original is, in my opinion, thievery. But regardless of the belief of the viewer one has to admit that the argument, and they way it is presented, is both convincing and entertaining. Ultimately, that really is all an entertaining film needs to be, and F for Fake succeeds wonderfully.

Analysis by a lawyer: Richard Stracke

Analysis by a lawyer: Richard Stracke

Orson Welles’ final completed film is a cinematic essay on the nature of art and the role of the author. In discarding traditional narrative, Welles was able to blend footage from a number of sources and perspectives. He leaves audiences with a film that is both fascinatingly multi-dimensional and at times frustratingly vacant.

Perhaps most fascinating is Welles’ examination of his great successes- the War of the Worlds broadcast and Citizen Kane. When he discusses the preliminary plans for his debut film, he notes that he originally intended to document the bizarre life of Howard Hughes. Whether it is true or not, I can’t be sure, but by raising the issue, Welles suggests that one of the central figures of F For Fake was the focus of a lifelong fascination. That his final film finally addressed this mystery is oddly satisfying. Hughes may not be the film’s central focus, but like Welles’ own mysterious history, he casts a shadow over the film. For me, the “Citizen Hughes” sequences were among the best of the film. They recaptured the grandiosely obtuse language of CK’s newsreels and forced me to contemplate whether the film could have been as successful with another eccentric tycoon at its center.

Although his curtained hotel rooms may not share the grandeur of Kane’s Xanadu, they achieve the same purpose. They permit eccentric failures- men whose public acts had long since become overshadowed by their undisclosed private lives- to captivate the world through inaction. Welles was not quite so reclusive, but he left behind a string of unfinished projects and like Hughes and Kane, started at the top and slowly collapsed under the weight of his own success. Interestingly, the opening moments of the Criterion commentary (all that I had time to listen to) note that the small child in the opening scenes is yet another manifestation of Orson’s attempts to recapture his past- another fruitless desire that harkens back to Kane.

Although his curtained hotel rooms may not share the grandeur of Kane’s Xanadu, they achieve the same purpose. They permit eccentric failures- men whose public acts had long since become overshadowed by their undisclosed private lives- to captivate the world through inaction. Welles was not quite so reclusive, but he left behind a string of unfinished projects and like Hughes and Kane, started at the top and slowly collapsed under the weight of his own success. Interestingly, the opening moments of the Criterion commentary (all that I had time to listen to) note that the small child in the opening scenes is yet another manifestation of Orson’s attempts to recapture his past- another fruitless desire that harkens back to Kane.

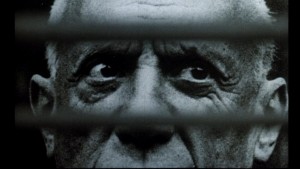

The discussion of Hughes and his alleged biographer open the door to another of the film’s central character- the Ibizan art forger. I was unfamiliar with his story, but it raised fascinating issues of “value” and the idea of authorship. Although I would certainly be furious if I were duped by such a man, the idea that someone could recreate masterworks so effortlessly and with such bravado does make him something of a ‘hero’ in my eyes. I won’t bore any of you with the tedium of copyright law, but there is a general principle that anything “original” created by another individual through their own creativity should be protected by law. The common illustration is that if you were to compose Keats’ “Ode to a Grecian Urn” on your own & could prove that you have neither knowledge nor access to the original, you could receive copyright protection for it as an original work. Not being familiar enough with the entire oeuvres of Modigliani/Matisse/Picasso etc., I’m not sure if de Hory was simply copying works that he’d seen or if he was able, via an innate understanding of the artists, creating works that looked exactly like what the other men would have made. Setting aside his intent to trick/possible profit motives, such a skill is extremely laudable. Curiously, de Hory was, by his own admission, unable to sell his own work. He lacked a vision of his own. The name and author are escaping me, but his situation reminded my of a relatively famous Pre-Raphaelite poem- one involving a man who can draw the perfect line, but lacks the heart to bring his figures to life. Which category de Hory fits into is up for argument.

As far as the rest of the film goes, I loved the opening ‘magic of the cinema’ type of scenes. The ogling scene was a highlight for me. More interesting than the fact that an attractive woman drew the stares of all manner of Italian men (hardly a shock!) was Welles’ playful treatment of the subject. He’s well aware of the way that cinema can manipulate our emotions. The sequence is great example of how the camera’s gaze and rhythmic cutting can excite the audience without so much as a word or ‘action’.

As far as the rest of the film goes, I loved the opening ‘magic of the cinema’ type of scenes. The ogling scene was a highlight for me. More interesting than the fact that an attractive woman drew the stares of all manner of Italian men (hardly a shock!) was Welles’ playful treatment of the subject. He’s well aware of the way that cinema can manipulate our emotions. The sequence is great example of how the camera’s gaze and rhythmic cutting can excite the audience without so much as a word or ‘action’.

While I enjoyed the opening, the last major sequence (return of the girl) was less satisfying. I didn’t think of it until Orson mentioned it, but while the first hour or so were “truth”, the scene that fell flattest for me was the “fake” one. I did enjoy the editing- Picasso observing- but the scene where Welles and the girl were conversing (in similar attire, no less) didn’t connect with me. Could truth really be more exciting than fiction?

Analysis by an elitist: Adam Lippe

Analysis by an elitist: Adam Lippe

The subtle difference between the self-satisfied smugness and back slapping cleverness of Orson Welles’ F For Fake and that of Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Twelve is nearly imperceptible. Welles’ assurance that you will be enthralled by his every word and oversized gesture, fascinated by his jet-setting among the rich and famous of the art world, the life of the party (watch the ladies fawn over him as he weaves his yarn over a steak and lobster dinner!) is so arrogant, so refreshingly contemptuous, pre-dating Michael Bay by 25 years, that you would be hard pressed to avoid giving him a round of applause…if you weren’t sure he was doing that for himself every time he called, “cut.”

Watch him in his cane and cloak Third Man ensemble, pseudo-self-mockingly referring to himself as a phony and a charlatan, just for an excuse for a quick greatest hits package of his career! Listen to him over-pronounce the word biography, every chance he gets! Smile as he constantly repeats that his story “is coming to an end” or “inappropriate for our current musings!”

Is the audience part of the joke, or the joke itself? The reveal in the conclusion, that, like his own The Lady From Shanghai, it’s all a house of mirrors, is rather empty, and causes the viewer to shrug its shoulders. It has always been true that the person most impressed with a magician’s trick is the magician himself.

Is the audience part of the joke, or the joke itself? The reveal in the conclusion, that, like his own The Lady From Shanghai, it’s all a house of mirrors, is rather empty, and causes the viewer to shrug its shoulders. It has always been true that the person most impressed with a magician’s trick is the magician himself.

It is unclear if Welles is totally aware of this fact. While there doesn’t have to be a wink to make it evident, his attitude, pretentious references to Hemingway, and the deeply whispered voiceover – filled to the brim with long, dramatic pauses – indicate that was taking himself seriously. Especially notable is the way that he constantly refers to the various projects he was working on simultaneous to coming across Elmyr and Irving’s stories, as if it were an attempt to show how busy he was. Though adding himself into the mix might appear to be a way for him to list his resume, it seems more like it was an attempt to stretch the running time to feature length.

At its essence, the three stories are thin on incident and character, worthy of perhaps ½ an hour on 60 Minutes, in total, not each. The repetition of seemingly extraneous clips of Elmyr entertaining at parties and restaurants and Irving staring glibly at the camera grows quickly tiresome. Assuming the audience had far too much previous knowledge of his subjects, Welles waits too long before explaining the details of the connections to Howard Hughes and the painters that Elmyr forges. And when he does get there, he only skims the edges.

At its essence, the three stories are thin on incident and character, worthy of perhaps ½ an hour on 60 Minutes, in total, not each. The repetition of seemingly extraneous clips of Elmyr entertaining at parties and restaurants and Irving staring glibly at the camera grows quickly tiresome. Assuming the audience had far too much previous knowledge of his subjects, Welles waits too long before explaining the details of the connections to Howard Hughes and the painters that Elmyr forges. And when he does get there, he only skims the edges.

From all we learn of Irving, he was just some guy who wrote a book about a fraudulent painter (of which we frustratingly learn no details of its contents, other than the subject), and then got the idea to write a fictional biography of Howard Hughes. The fringes are not even hinted at, that Irving’s pseudo-biography was not just front page headlines, but its claims of $400,000 bribes from Hughes to then president Nixon became a huge scandal. Or even that the book was never published. Unbeknownst to Welles at the time, Nixon’s domestic affairs advisor, John Ehrlichman, claimed that the information was so close to reality that it inspired Watergate, as he was concerned what Irving might have told the Democrats about the reason for the bribes. Supposedly, the 17 minute gap in Nixon’s audio tapes dealt with the bribes.

At least Elmyr, as an example, develops Welles’ point about the minor difference between reality and a supposed fake. While we are shown how Elmyr’s lack of personal vision frustrated him as an original painter and how he currently lives a sad, penniless life, it doesn’t add up that he would be poor. He admits that his paintings, real or not, still go for $15,000 – something he spends no more than an hour on. So if he can polish off so many so quickly, where is this purported poverty coming from?

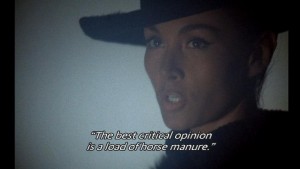

In the end, Welles’ sleight of hand is what is most important to him, and F For Fake is merely a dig at the rich (studio heads who never gave him a proper shot after Citizen Kane) with expensive paintings on their wall, without understanding the meaning of them, and the fallibility of critics and experts, whose credibility is all they have, until they are proven wrong. The film is a dare, but the viewers are the fools if they make the choice of either taking him seriously or not. Both options are incorrect.

In the end, Welles’ sleight of hand is what is most important to him, and F For Fake is merely a dig at the rich (studio heads who never gave him a proper shot after Citizen Kane) with expensive paintings on their wall, without understanding the meaning of them, and the fallibility of critics and experts, whose credibility is all they have, until they are proven wrong. The film is a dare, but the viewers are the fools if they make the choice of either taking him seriously or not. Both options are incorrect.

Richard It’s hard to know where to start, but I spent some time in my essay discussing the biographical elements, so, if everyone would like to start with that.

Rhett I thought it was very interesting the way Welles wove himself into the narrative.

Shawn I agree, particularly as a magician.

Rhett I took the whole thing as a possible metaphor for Welles’ time in Hollywood.

Adam as did I, but the movie seemed self-serving in that way like an ad for possible future projects to studios and/or producers.

Rhett They made him feel as if he were a fraud, a sell-out making copies of other people’s movies.

Richard I only had time to listen to the first few minutes of commentary, but it mentioned that the child in the opening scene- the one he does coin/key tricks with was also supposed to be some kind of stand in for him.

Shawn It is actually Oja’s son.

Adam What was the overall purpose of the film?

Rhett Considering how masterful the editing is for the opening sequence of Oja, it is hard to imagine how Hollywood never really took the bait, Adam.

Richard Also, if true, his initial interest in doing his first film about Hughes and then discussing him in his final finished film; Very circular- if true

Adam If all he wanted to do was prove the subtle differences between forgery and reality.

Rhett Very true, Richard.

Richard Adam- I had trouble deciding on its purpose aside from a game.

Richard Adam- I had trouble deciding on its purpose aside from a game.

Adam Couldn’t it have been either more succinct or shorter?

Richard The later scenes did drag.

Shawn I thought, like Adam said, it was mostly a self-serving essay on trickery, and acceptance of trickery.

Rhett I think he wanted to expose the connotations involved in watching a documentary in that you assume objective truth, willing to believe everything that is shown on screen

Adam The problem was, most of what was on screen, was not interesting. There was not enough detail and a lot of repetition.

Rhett Considering that the film was made on the fringe of Vietnam and cinema verite, it was a pretty relevant message.

Shawn So by faking a third of the film, did he prove his point?

Adam He covers two fascinating stories, but does not delve into them.

Richard I was somewhat surprised that the scenes that I liked the least were admittedly totally false- the meeting with Welles and Oja toward the end- when they were dressed similarly.

Rhett I thought he did, Shawn. He had me fooled.

Shawn I admit, I fell for the trick as well.

Rhett I agree, Adam, the actual documentary footage seemed poorly organized and not as involving as it should have been.

Richard Same with me, Rhett. I fell for it.

Adam I had prior knowledge.

Rhett Although he does admit this himself at the start, apologizing for how haphazard the editing is.

Adam So I was not fooled, but it actually seemed the most believable of the three.

Rhett Yeah, it did, Adam, probably because it was the most planned.

Shawn I agree with that. The Hughes autobiography bit boggles my mind.

Shawn I agree with that. The Hughes autobiography bit boggles my mind.

Adam The Irving segment really should have been more detailed. There is a fascinating story behind that.

Richard Do you think that some of the repetition could have been do to the fact that a lot of the interviews and such were taken from someone else’s project- just edited by Welles?

Adam The book has still never been published but he never got into that. The book might have even caused Watergate, which Welles couldn’t have known.

Rhett I was going to say that, Richard, but you’d think having all that footage beforehand would actually make the footage more concise.

Adam But even an inkling of the impact should have been hinted at.

Richard Good point, Rhett.

Adam Well, Rhett, he would be limited by what was already shot.

Rhett Yes, but he was able to edit himself into the footage to fill in loose ends but he still didn’t do that good of a job at doing so.

Adam I would have watched an entire 85 minute movie of just goofy pictures of Picasso.

Rhett I was always more captivated by the autobiographical element anyway though, so I didn’t care if the rest of it wasn’t all that clear cut.

Richard The editing was great throughout- especially Picasso and the early scene with the girl walking and the observers.

Shawn Yes, I saw the whole film more as it related to Welles then as it related to reality.

Rhett Yeah, Richard, I was absolutely amazed at the Oja sequence and I think that was the intent.

Richard Yeah, I was sucked right into it and it wasn’t just because she was hot.

Shawn I loved both Oja sequences, although I don’t think that she had a very attractive face.

Shawn I loved both Oja sequences, although I don’t think that she had a very attractive face.

Richard It really shows that editing is as, if not more, important than what’s on screen.

Rhett To show how the viewer can be fooled by what is on the surface, just like an audience member always focuses on the assistant or other irrelevant details during a magic trick.

Adam But he was not helped by the lecherous credits while he used that to establish her for later on. It went on far past his point.

Shawn I never felt that the movie dragged. I was entertained throughout.

Rhett What do you think Welles was trying to say about forgery? Do you think he saw it as an art form or not?

Richard I was most interested in his ideas about valuation and experts, how something could be amazing- as the forgeries were but its value would depend solely on what someone else thinks – who arguably can’t create on his/her own.

Adam That was a dig at critics and teachers.

Rhett Perhaps doing so was his way of justifying his Hollywood stuff. That had me thinking about Van Sant’s Psycho, since that is probably the most notorious cinema forgery of all time.

Shawn He calls himself a charlatan, and explains exactly why he is one.

Richard How were most of his films received critically? I know there were issues with them being cut- Touch of Evil for example. That would explain the dislike for experts.

Adam Ambersons, as I remember, was trashed in the 88 minute version.

Rhett Welles probably would have liked it.

Shawn Van Sant’s Psycho isn’t a forgery though. Van Sant never once stated that it was “his” movie. And remember, Elmyr was not really forging. He wasn’t repainting the Mona Lisa, he was creating new art.

Richard Shawn- could that just be a technicality? Like the artist not signing?

Adam But, he was signing it, he just claimed he wasn’t.

Rhett Well, it’s Van Sant’s name as director on the credits, not Hitchcock but still, basically a shot for shot rehash.

Adam Rhett, would the Psycho remake been better if it had been shot Dogme style? No director credit?

Adam Rhett, would the Psycho remake been better if it had been shot Dogme style? No director credit?

Rhett I am not sure.

Shawn But all throughout 1998 Van Sant always called it “my version of Psycho” the DVD says that it is a remake, and the property belongs to Universal, who allowed it.

Rhett It would be even more interesting if Hitchcock received the director’s credit.

Richard On the topic of Elmyr- he reminded me of the subject of a pre-Raphaelite poem. I can’t remember name/author, but it was about an artist who could draw the perfect line/form- but his work had no heart. No voice of his own.

Adam There would have been a further outcry if it had been given Hitchcock’s credit.

Rhett I thought it was interesting how de Hory kept burning his forgeries moments after painting them.

Shawn I think that Hitchcock would have to leave the director’s guild from beyond the grave.

Rhett It was like he just did it to place himself in the shoes of others, like a chameleon or something. The money didn’t really mean anything to him, it seems.

Richard How do you think Welles felt about this lack of ‘auteur-ism’? He admitted that ‘his’ work wouldn’t sell.

Shawn Well it was mentioned that he really didn’t see that much money from his paintings. But you can’t really doubt his talent for mimicking.

Adam And what level of bitter was there in Welles when he talked about being a failed teenage painter in Ireland?

Shawn I think that Welles was still playing Harry Lime in this movie.

Adam Yes, the uniform certainly hinted at that.

Shawn So sly… so smart.

Rhett Well, if Tarantino can make auteurism out of redoing pop culture’s stories, then why couldn’t someone be an auteur in their constant obsession with redoing previous art?

Rhett Well, if Tarantino can make auteurism out of redoing pop culture’s stories, then why couldn’t someone be an auteur in their constant obsession with redoing previous art?

Adam Other than the Seagal method of wearing a huge coat to hide your girth.

Shawn What was the real story behind Welles obesity?

Adam Too many green peas.

Shawn He got fat, sure. But he looked 50 times better here then in Touch of Evil.

Richard I’m not sure. I thought he looked surprisingly good here.

Rhett That was because his ego had flared up on the set of Touch of Evil.

Richard Maybe it was the coat.

Adam Ego = saturated fats?

Rhett No, Adam. Carbs.

Shawn It’s not just the coat, his face seemed less fat than in Touch of Evil. Adam, you mentioned this as an ad for future projects. The commentary mentions this.

Rhett Transformers: The Movie? Unicron seemed drawn bigger than usual in the film version as well.

Adam Shawn, does it get into the purpose of the film, other than financial? Because he easily exposes the problem with experts but the rest of it wavers.

Rhett I thought it was interesting the way Welles used the quote from Picasso saying that, essentially, artists can make forgeries of their own work.

Shawn It really doesn’t go there, Adam.

Rhett Maybe a forgery artist like de Hory could put more effort and artistry in a fake copy of Picasso than Picasso could put into his own paintings.

Shawn The commentary is by Oja and someone else. Oja talks more or less about her relation to him.

Rhett Thus, art is not what is made, but the passion that goes into it.

Rhett Thus, art is not what is made, but the passion that goes into it.

Shawn Well de Hory thought he was doing the world a favour.

Richard Rhett- do you think a ‘fake’ Picasso would be anything motivated by profit or malaise- instead of true inspiration?

Adam But he was able to shoot off these paintings in an hour. How much passion could there have been?

Rhett Well, Adam, the way he talked about the painters, he seemed to really care about it, talking about each painter’s pitfall, and how he could do their own work better than them. Like when he said that one painter’s hand was too shaky.

Shawn He states, and I paraphrase, “Real paintings are rare, so I make more of them. If you like it you should have it.”

Adam Yes, but that seemed like arrogance and empty arrogance, at that.

Shawn No one burns anything they are passionate about.

Adam “I can’t do anything original, but I can do impressions.”

Shawn It is purely a “look at me” mentality.

Adam It’s like bragging about being Dana Carvey.

Richard Were his paintings all copies of work that they actually did- or done in the style and passed off as lost works?

Shawn The latter. They were original works disguised as lost.

Rhett Richard, I think a fake Picasso would be motivated just by boredom, doing a painting just because it is expected of him, rather than doing one because he feels the artistic urge to do so.

Shawn Which is why I said before that he wasn’t repainting the Mona Lisa.

Adam And since the motivation was purely financial, otherwise, why do it, I can’t sense any legit passion in it.

Shawn I did like the story of the one art collector whom he told “I found one in the drawer.”

Rhett Well, he didn’t really make much from it, so perhaps his passion was to bring lost works out there for others to finally enjoy. The Criterion of baroque art.

Shawn No, Criterion releases real movies. They don’t create new ones and say it is the lost Hitchcock film. Although they will release crap movies and make them seem worth watching.

Rhett Hey, there is extreme artistry in Armageddon.

Adam Is F For Fake hurt by stuff like House of Games? Even Gossip?

Adam Is F For Fake hurt by stuff like House of Games? Even Gossip?

Shawn Re: Salo: The 120 Days of Boredom

Adam The pull-the-curtain-back conclusion. Nine Queens and Criminal also pull the same trick.

Rhett The Usual Suspects?

Shawn Orson Welles should have skipped around in a circle like a schoolgirl saying “I fooled you! I fooled you!”

Rhett I mentioned that in my review, and I don’t think it hurts the film at all since F For Fake has substance to go along with the trick at the end.

Adam No, the ones I mention literally have a pull the curtain back to see the fakery conclusion.

Shawn It would have meant an automatic purchase if he did.

Rhett Since with or without the ending, it serves as a powerful epitaph for Welles on his career.

Shawn Yes, and the references to Kane and War of the Worlds were nice. Because they made sense.

Rhett I feel the urge to watch the whole thing again, which is something I generally cannot say about those other punch line films.

Richard Do you think that the original plan to use Hughes as the Kane subject was true? I haven’t read much about its pre-production.

Adam No, it wasn’t and apparently, that is what piqued Scorsese’s interest, and why he eventually made The Aviator.

Shawn But I always thought it was intended to be Hearst.

Rhett So he did lie in the first hour of F For Fake, then?

Adam When was it that he said that nothing else would be lied about in the next hour? It might have been after that.

Richard That’s what I was wondering Rhett. It didn’t seem to jive with what I’d heard elsewhere, but he did promise truth.

Rhett He said it after about five minutes.

Shawn I don’t recall, but I really have no way to prove him wrong about the Hughes comment. So I can’t exactly call it a lie.

Rhett It seems perfectly feasible that Welles could have had some early concept of making a film about Hughes.

Richard How eccentric was he known to be in 40-41? I know he paraded about with the girls and did his Aviator stuff, but was he known as a recluse yet?

Shawn It may have been something else before Kane, like a different project altogether. I haven’t seen Aviator yet. I don’t know that much about Hughes really, so I can’t help much.

Rhett No, I think the reclusive aspects came forth much later in life.

Adam Hughes would have just been a rich man trying to produce films at that point. Seems not like the best subject for a film. The casting of Cotton and Harvey in F For Fake was probably more about star power not because Welles could find a way to tie them in.

Shawn Richard do you still have the DVD?

Shawn Richard do you still have the DVD?

Richard Yeah.

Shawn I really liked the trailer. It was very pretentious, but enjoyable anyway.

Rhett Yes, I was amazed at the prospect of a 9 minute trailer.

Adam In terms of the movie, did you feel teased that there wasn’t more on Elmyr? And not more on Irving?

Rhett I knew absolutely nothing about it going in, so I was totally surprised with what transpired.

Richard Same with me.

Rhett I thought he covered de Hory well, but Irving was kind of just glossed over.

Adam But Welles should have detailed it a bit more within the film.

Shawn I agree, Irving should have a lot more developed.

Rhett I watched the film from a rip from Spanish television, so if anyone has any questions regarding Spanish subtitling, I am your man.

Shawn What colour were the subtitles?

Adam Light yellow.

Shawn I would have detracted an entire star.