Lost in Translation

“I have to leave, but I don’t want to.”

“I have to leave, but I don’t want to.”

“Then stay here… With me. We’ll start a jazz band.”

While I was watching Lost in Translation, I was often restless and fidgety, but not in an impatient way. I had the feeling that I had during certain parts of Noah Baumbach’s Kicking and Screaming where the characters despair of not knowing what to with their lives. As Chris Eigeman said in that movie, as a recent college graduate who realizes that once you finish school, you suddenly transform from a scholar on the brink of reaching your full potential, to an aimless loser adding yourself to the end of the unemployment line, “I wish I was just retiring. Like I worked for 50 years, and I was coming home after a lifetime of accomplishment.”

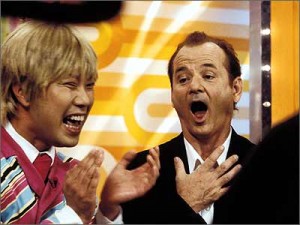

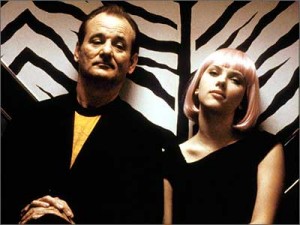

That aimless feeling is in every scene in Lost in Translation, where Scarlett Johanasson doesn’t know why she is where she is in life, and would hate to spend the rest of her time as a traveling wife to a successful photographer. Personally, I could understand her plight even more than Murray, who is stuck in Japan as a semi-washed up actor picking up a huge paycheck for a whiskey ad. The scenes with him attempting to fulfill the director’s wishes in the different ways to hold the whiskey glass to the looks he gives to the photographer trying to get him to act out other famous actor’s poses are genius, but more for the ways that Murray doesn’t do his expected routine, and uses the opportunity to express his gentle acceptance of his loss of control of his own life. He would express embarrassment to the multitude of people around him, if only he thought they might understand what he was trying to say.

That aimless feeling is in every scene in Lost in Translation, where Scarlett Johanasson doesn’t know why she is where she is in life, and would hate to spend the rest of her time as a traveling wife to a successful photographer. Personally, I could understand her plight even more than Murray, who is stuck in Japan as a semi-washed up actor picking up a huge paycheck for a whiskey ad. The scenes with him attempting to fulfill the director’s wishes in the different ways to hold the whiskey glass to the looks he gives to the photographer trying to get him to act out other famous actor’s poses are genius, but more for the ways that Murray doesn’t do his expected routine, and uses the opportunity to express his gentle acceptance of his loss of control of his own life. He would express embarrassment to the multitude of people around him, if only he thought they might understand what he was trying to say.

There’s also a bit of John Boorman’s Hell in the Pacific, where Lee Marvin and Toshiro Mifune are stuck on an island by themselves during WWII and neither know each other’s language. Boorman chose not to subtitle Mifune as he spoke Japanese to recreate for the audience the confusion that Marvin was going through. Murray has the same issue in Lost in Translation, as there are many scenes where he is forced to nod and smile, at first attempting to make an effort to understand what is being said through gestures or translators, and then as frustration sets in, trying to make a joke of it, to eventually not even bothering. Of course, this is a none-too-subtle analogy for how lost he is in his home life, where he seems not needed by a wife and kids who have learned to live without him, but somehow want to continue to pretend that they are a traditional family.

Basically each scene is a variation on itself, where Murray and Johansson give longing looks at each other, but not sexual looks, more of an understanding that they are in completely different points in their lives, but in the same points in their cycle of repetition. There’s little of actual importance that is expressed verbally, but this is one of the only movies I’ve ever seen, that doesn’t feel the need to have characters spout constantly witty dialogue to successfully establish a close bond between people. It has an odd realism in that fact because often, in real life, it’s more the mutual experience that draws people together, and it doesn’t have to be a series of monumental events, rather than some profound insight that they find in one another.

Basically each scene is a variation on itself, where Murray and Johansson give longing looks at each other, but not sexual looks, more of an understanding that they are in completely different points in their lives, but in the same points in their cycle of repetition. There’s little of actual importance that is expressed verbally, but this is one of the only movies I’ve ever seen, that doesn’t feel the need to have characters spout constantly witty dialogue to successfully establish a close bond between people. It has an odd realism in that fact because often, in real life, it’s more the mutual experience that draws people together, and it doesn’t have to be a series of monumental events, rather than some profound insight that they find in one another.

There’s a scene in a strip club that is the only reason the film got an R rating, and even though it doesn’t have any purpose on the movie, and results in a nice, but easy joke, I think if it had been cut it would have lost the casual dreaminess that is the mood of each scene.