Somers Town

The ability of some films to knock you into a blissful trance despite the absence of anything substantial occurring on screen is not just a credit to the filmmakers but a nearly unexplainable phenomenon. Jim Jarmusch made Stranger Than Paradise, a movie about nothing people, doing nothing. The scenes are long blackout sketches where the camera rarely, if ever moves, and the dialogue is dull on the surface. And yet, the movie is hilarious. Jarmusch pulled off this same feat in Down By Law, but the droll tricks started to wear thin by Mystery Train, which plays more as if it weren’t sketched in and lazily thrown together, as opposed to it just being the character’s inexpressiveness. Each of Jarmusch’s films that followed skirted this same line, distinguished only by the style of actor chosen and if they could work with Jarmusch’s formula. It worked with Roberto Benigni in Night on Earth where his manic energy plays as juxtaposition to the laconic filmmaking and with both Forest Whitaker in Ghost Dog and Bill Murray in Broken Flowers, for their quiet underplaying. When the acting styles don’t mesh with Jarmusch’s laid-back emptiness, such as with Winona Ryder in Night on Earth and any of the actors playing mobsters in Ghost Dog, it is overwrought, embarrassing, and obnoxious.

The ability of some films to knock you into a blissful trance despite the absence of anything substantial occurring on screen is not just a credit to the filmmakers but a nearly unexplainable phenomenon. Jim Jarmusch made Stranger Than Paradise, a movie about nothing people, doing nothing. The scenes are long blackout sketches where the camera rarely, if ever moves, and the dialogue is dull on the surface. And yet, the movie is hilarious. Jarmusch pulled off this same feat in Down By Law, but the droll tricks started to wear thin by Mystery Train, which plays more as if it weren’t sketched in and lazily thrown together, as opposed to it just being the character’s inexpressiveness. Each of Jarmusch’s films that followed skirted this same line, distinguished only by the style of actor chosen and if they could work with Jarmusch’s formula. It worked with Roberto Benigni in Night on Earth where his manic energy plays as juxtaposition to the laconic filmmaking and with both Forest Whitaker in Ghost Dog and Bill Murray in Broken Flowers, for their quiet underplaying. When the acting styles don’t mesh with Jarmusch’s laid-back emptiness, such as with Winona Ryder in Night on Earth and any of the actors playing mobsters in Ghost Dog, it is overwrought, embarrassing, and obnoxious.

With his new film Somers Town, director Shane Meadows manages to pull an early Jarmusch. Utilizing none of the energy Meadows thrived in with his brilliant This Is England, about burgeoning skinheads in England, circa 1983, Meadows doesn’t even bother filling in the backgrounds for his characters in Somers Town. We see Thomas Turgoose (playing Tomo), the neo-Nazi in training from This Is England getting on a train with only a bag and a bad haircut, and while throughout Somers Town he claims he has no family or place to live, we aren’t shown anything to contradict him. Sure, he’s a cocky, whiny, uncouth ingrate. But we don’t know if his instinct to grab things away from people when they are looking and steal from them when they aren’t was his way of dealing with growing up in a large, poor family in a small house, having to fight for scraps of food. Meadows lets you fill in certain blanks without making you do all the work. The other major character, Marek (played by Piotr Jagiello) a young Polish immigrant living with his alcoholic father, has hints of loneliness and mother figure fantasies. But we never quite learn why his parents are divorced, only that they argued a lot.

With his new film Somers Town, director Shane Meadows manages to pull an early Jarmusch. Utilizing none of the energy Meadows thrived in with his brilliant This Is England, about burgeoning skinheads in England, circa 1983, Meadows doesn’t even bother filling in the backgrounds for his characters in Somers Town. We see Thomas Turgoose (playing Tomo), the neo-Nazi in training from This Is England getting on a train with only a bag and a bad haircut, and while throughout Somers Town he claims he has no family or place to live, we aren’t shown anything to contradict him. Sure, he’s a cocky, whiny, uncouth ingrate. But we don’t know if his instinct to grab things away from people when they are looking and steal from them when they aren’t was his way of dealing with growing up in a large, poor family in a small house, having to fight for scraps of food. Meadows lets you fill in certain blanks without making you do all the work. The other major character, Marek (played by Piotr Jagiello) a young Polish immigrant living with his alcoholic father, has hints of loneliness and mother figure fantasies. But we never quite learn why his parents are divorced, only that they argued a lot.

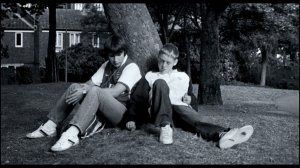

The fuzziness of some of the details in Somers Town are greatly aided by the gorgeous black and white photography, which has that slight bluish tint of the b&w sequences in Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire, which similarly took place in working class areas of a European country. Tomo, desperate for any kind of interaction, ends up as friends with Marek out of mutual boredom, (it isn’t specified, but it appears that they are on summer break from school) and both fall in love with a French waitress that they dote on. The realism mixed with the dreamy feel sits just right with the random turns of the story, such as Tomo stealing a bag of clothes from a Laundromat because he doesn’t have anything to wear, or when the pair are paid to sit in deck chairs. There’s a constant feeling that the boys are overcoming their dreadful circumstances by adding as many banalities to their lives as they can, as happiness is not an attainable goal. Even Tomo’s thievery isn’t a matter of creating danger and excitement so much as an odd way to meet people (and it results in dialogue from a heavyset older gentleman angered by their noise and disruption in a “private” area, “I’ll remember your face, I’ve got a photographic memory and everything”).

The fuzziness of some of the details in Somers Town are greatly aided by the gorgeous black and white photography, which has that slight bluish tint of the b&w sequences in Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire, which similarly took place in working class areas of a European country. Tomo, desperate for any kind of interaction, ends up as friends with Marek out of mutual boredom, (it isn’t specified, but it appears that they are on summer break from school) and both fall in love with a French waitress that they dote on. The realism mixed with the dreamy feel sits just right with the random turns of the story, such as Tomo stealing a bag of clothes from a Laundromat because he doesn’t have anything to wear, or when the pair are paid to sit in deck chairs. There’s a constant feeling that the boys are overcoming their dreadful circumstances by adding as many banalities to their lives as they can, as happiness is not an attainable goal. Even Tomo’s thievery isn’t a matter of creating danger and excitement so much as an odd way to meet people (and it results in dialogue from a heavyset older gentleman angered by their noise and disruption in a “private” area, “I’ll remember your face, I’ve got a photographic memory and everything”).

That’s not to suggest that Somers Town is some sort of masterpiece of the slight, it is just a scrappy and mildly charming movie. But mostly very short, small, and meek. You don’t want to pick on it too much because it’s insecure, just like its characters.