I Come With the Rain

It’s been said, by a much wiser man than I, that Charles Bronson looked like Mr. Potato Head. This was especially true in his later years in front of the camera, mailing it in while working with J. Lee Thompson and Michael Winner and Cannon Films in the 1980s on such sleazy and workmanlike films as 10 to Midnight, Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects, Death Wish III, etc. However, as a counter to this man’s Mr. Potato Head argument, I suggested that Bronson, with his salt and pepper hair and eyes squinting through his weathered face, looked more like a wrinkled old Chinese woman with a mustache.

It’s been said, by a much wiser man than I, that Charles Bronson looked like Mr. Potato Head. This was especially true in his later years in front of the camera, mailing it in while working with J. Lee Thompson and Michael Winner and Cannon Films in the 1980s on such sleazy and workmanlike films as 10 to Midnight, Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects, Death Wish III, etc. However, as a counter to this man’s Mr. Potato Head argument, I suggested that Bronson, with his salt and pepper hair and eyes squinting through his weathered face, looked more like a wrinkled old Chinese woman with a mustache.

The old Chinese woman analogy was especially true in one of Bronson’s later vehicles, the marvelously idiotic Assassination (one of two films he made with Peter Hunt in the 1980s, the other being Death Hunt), as Bronson, romancing a much younger [Asian] girlfriend, trying to compensate for looking so aged and out of place while attempting to protect the First Lady, finds himself ensconced in some of the most haphazardly edited chase sequences in any film that might refer to itself as professional. Whether it’s a boat chase, a car chase, or a helicopter chase, rest assured that top speed will be 4 miles per hour.

The old Chinese woman analogy was especially true in one of Bronson’s later vehicles, the marvelously idiotic Assassination (one of two films he made with Peter Hunt in the 1980s, the other being Death Hunt), as Bronson, romancing a much younger [Asian] girlfriend, trying to compensate for looking so aged and out of place while attempting to protect the First Lady, finds himself ensconced in some of the most haphazardly edited chase sequences in any film that might refer to itself as professional. Whether it’s a boat chase, a car chase, or a helicopter chase, rest assured that top speed will be 4 miles per hour.

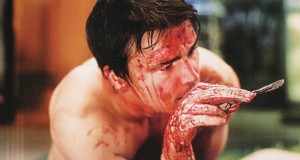

In Anh Hung Tran’s I Come With the Rain, Josh Hartnett is like our surrogate Bronson, hidden behind a squirrely mustache that would shame a Mexican teenager just hitting puberty. Hartnett, playing an ex-cop now PI, is totally out of place in the film, which helps with his mission of trying to track down the son of a pharmaceutical magnate, who may or may not be doing his best Jesus impression, in a tent on the outskirts of Hong Kong. Haunted by cloudy flashbacks of his showdown with a serial killer (Elias Koteas), Hartnett is perpetually bewildered, staring at the answers to his questions without ever registering them. He’s a lone white man surrounded by Asians and it’s always raining. Frankly, he’s Harrison Ford’s character of Deckard in Blade Runner, and Tran accentuates the similarity by repeatedly focusing on rain-soaked cityscapes in Hong Kong. It’s probably a coincidence that Deckard’s liaison and co-worker who makes convenient appearances was played by Edward James Olmos, who looks an awful lot like Charles Bronson.

In Anh Hung Tran’s I Come With the Rain, Josh Hartnett is like our surrogate Bronson, hidden behind a squirrely mustache that would shame a Mexican teenager just hitting puberty. Hartnett, playing an ex-cop now PI, is totally out of place in the film, which helps with his mission of trying to track down the son of a pharmaceutical magnate, who may or may not be doing his best Jesus impression, in a tent on the outskirts of Hong Kong. Haunted by cloudy flashbacks of his showdown with a serial killer (Elias Koteas), Hartnett is perpetually bewildered, staring at the answers to his questions without ever registering them. He’s a lone white man surrounded by Asians and it’s always raining. Frankly, he’s Harrison Ford’s character of Deckard in Blade Runner, and Tran accentuates the similarity by repeatedly focusing on rain-soaked cityscapes in Hong Kong. It’s probably a coincidence that Deckard’s liaison and co-worker who makes convenient appearances was played by Edward James Olmos, who looks an awful lot like Charles Bronson.

Our disorientation throughout I Come With the Rain is exacerbated by frequent surreal imagery that looks like very poorly matted green screen work but most likely is just a strange use of wide angle and fish eyed lenses. These images mostly rear their head in what are just standard expositional conversations, maybe to distract us from all of the actors (save for Hartnett) speaking English when it is clearly not their native language, maybe as Tran’s way of amusing himself to get past the story points. It’s certainly odd to suddenly be distracted first by what looks like one character’s glass eye, and then notice the waterfall behind him, and then recognize that he appears to be floating, but that’s really just our imagination. Maybe. It certainly gets us past the very minimal dialogue and the unnecessarily complicated story.

Our disorientation throughout I Come With the Rain is exacerbated by frequent surreal imagery that looks like very poorly matted green screen work but most likely is just a strange use of wide angle and fish eyed lenses. These images mostly rear their head in what are just standard expositional conversations, maybe to distract us from all of the actors (save for Hartnett) speaking English when it is clearly not their native language, maybe as Tran’s way of amusing himself to get past the story points. It’s certainly odd to suddenly be distracted first by what looks like one character’s glass eye, and then notice the waterfall behind him, and then recognize that he appears to be floating, but that’s really just our imagination. Maybe. It certainly gets us past the very minimal dialogue and the unnecessarily complicated story.

Was Tran more concerned with his unsubtle religious allegories? The father is never seen, only heard, and his line of work is medicine, but he asks Kline (Hartnett) to find his son. Kline is likely an allusion to the pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, and the unseen father is clearly meant to represent God, searching for his son who heals the sick through spiritual means. The serial killer is obsessed with creating his distorted view of humanity through suffering and pain, and on and on. The tenuous connections to The Cell (especially in Koteas’ scenes which linger on his grotesque sculptures) in a visual sense are a strange coincidence, since, like with Tarsem and The Cell, Tran brought his pet themes and imagery with him and the fact that he got the money to make a serial killer film was incidental. But Tarsem was working with someone else’s rotten screenplay (and he was more than happy to point out its shortcomings), and in I Come With the Rain, Tran is working with his own material and so the genre requirements are of his own making. Perhaps final cut eluded him; Tran had to battle the producers in court for control of I Come With the Rain, which might explain some of the visual concessions with Hartnett moping on top of a building and the HD-cam is used to ape 2006’s Miami Vice in the pixelated and muddy look. I’m sure both Michael Mann and whomever made the decisions on I Come With the Rain thought the images were striking and edgy, but in Tran’s film they’re totally at odds with the otherworldly crispness of the rest of the imagery.

Was Tran more concerned with his unsubtle religious allegories? The father is never seen, only heard, and his line of work is medicine, but he asks Kline (Hartnett) to find his son. Kline is likely an allusion to the pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, and the unseen father is clearly meant to represent God, searching for his son who heals the sick through spiritual means. The serial killer is obsessed with creating his distorted view of humanity through suffering and pain, and on and on. The tenuous connections to The Cell (especially in Koteas’ scenes which linger on his grotesque sculptures) in a visual sense are a strange coincidence, since, like with Tarsem and The Cell, Tran brought his pet themes and imagery with him and the fact that he got the money to make a serial killer film was incidental. But Tarsem was working with someone else’s rotten screenplay (and he was more than happy to point out its shortcomings), and in I Come With the Rain, Tran is working with his own material and so the genre requirements are of his own making. Perhaps final cut eluded him; Tran had to battle the producers in court for control of I Come With the Rain, which might explain some of the visual concessions with Hartnett moping on top of a building and the HD-cam is used to ape 2006’s Miami Vice in the pixelated and muddy look. I’m sure both Michael Mann and whomever made the decisions on I Come With the Rain thought the images were striking and edgy, but in Tran’s film they’re totally at odds with the otherworldly crispness of the rest of the imagery.

If Tran was interested in duplicating a mainstream American filmmaker’s experimentation with HD video, he ought to have skipped Michael Mann and gone straight to Robert Rodriguez and asked him about Sin City. Josh Hartnett was even in Sin City, he’s part of the opening reel that Rodriguez put together for investors. Rodriguez created a palatable unreality coated with unending violence in Sin City, so there was no need to add any verité elements to remind us we’re watching a movie. Besides, Hartnett’s casting in I Come With the Rain is what sets it apart from any old DTV serial killer movie that rips off Seven, like Russell Mulcahy’s Resurrection (which is about a killer taking his victim’s body parts in order to put together his version of Jesus), because the convolutions that the Rain goes through to come up with an ending are entirely conspicuous. The fact that Tran had to wait 8 years to make I Come With the Rain, after 2000’s Vertical Ray of the Sun, is a shame and his frustration comes out in the crasser elements of Rain, such as in an entirely extraneous scene where Hartnett, unable to decipher the puzzle in front of him, angrily throws his cup-a-noodle at a collage put together by the serial killer. But, though he left behind the gentle touch he showed in Vertical Ray of the Sun, like his other films, Tran’s accomplishments in I Come With the Rain are in the small, quiet moments of reflection. In this case, the characters are pensive about their pain, and those who ignore the pain they cause others are doomed to be emotionally cut off. Sometimes, literally cut off.

If Tran was interested in duplicating a mainstream American filmmaker’s experimentation with HD video, he ought to have skipped Michael Mann and gone straight to Robert Rodriguez and asked him about Sin City. Josh Hartnett was even in Sin City, he’s part of the opening reel that Rodriguez put together for investors. Rodriguez created a palatable unreality coated with unending violence in Sin City, so there was no need to add any verité elements to remind us we’re watching a movie. Besides, Hartnett’s casting in I Come With the Rain is what sets it apart from any old DTV serial killer movie that rips off Seven, like Russell Mulcahy’s Resurrection (which is about a killer taking his victim’s body parts in order to put together his version of Jesus), because the convolutions that the Rain goes through to come up with an ending are entirely conspicuous. The fact that Tran had to wait 8 years to make I Come With the Rain, after 2000’s Vertical Ray of the Sun, is a shame and his frustration comes out in the crasser elements of Rain, such as in an entirely extraneous scene where Hartnett, unable to decipher the puzzle in front of him, angrily throws his cup-a-noodle at a collage put together by the serial killer. But, though he left behind the gentle touch he showed in Vertical Ray of the Sun, like his other films, Tran’s accomplishments in I Come With the Rain are in the small, quiet moments of reflection. In this case, the characters are pensive about their pain, and those who ignore the pain they cause others are doomed to be emotionally cut off. Sometimes, literally cut off.

Bad puns are awesome.