Dirty Harry vs. The French Connection: The Fascist Cop Movies of 1971

The late 1960’s were a troubled time for the major studios of Hollywood. Expensive musicals like Hello Dolly had failed as had pricey westerns like Paint Your Wagon. The success of Easy Rider was considered a breakthrough and set up the director-centric 1970’s spawning one crafty film nerd filmmaker after another, such as Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg. As covered extensively in Peter Biskind’s fascinating and thorough book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Hollywood’s confusion over how to sell their product to the mainstream caused this shift, as the notion of a studio factory disappeared resulting in more personal projects. Unable to satisfy the new counterculture and hippie audiences, as well as how to deal with the, by that time, endless and unpopular Vietnam War, the studios eventually gave up trying to control every aspect of production, sometimes even going as far as throwing a few million dollars at an up and coming director and telling him to come back with something they could market. However, the studios’ initial reaction was more of anger and panic, a resentment of the audiences they could no longer please.

The late 1960’s were a troubled time for the major studios of Hollywood. Expensive musicals like Hello Dolly had failed as had pricey westerns like Paint Your Wagon. The success of Easy Rider was considered a breakthrough and set up the director-centric 1970’s spawning one crafty film nerd filmmaker after another, such as Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg. As covered extensively in Peter Biskind’s fascinating and thorough book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Hollywood’s confusion over how to sell their product to the mainstream caused this shift, as the notion of a studio factory disappeared resulting in more personal projects. Unable to satisfy the new counterculture and hippie audiences, as well as how to deal with the, by that time, endless and unpopular Vietnam War, the studios eventually gave up trying to control every aspect of production, sometimes even going as far as throwing a few million dollars at an up and coming director and telling him to come back with something they could market. However, the studios’ initial reaction was more of anger and panic, a resentment of the audiences they could no longer please.

1971 was an important year for this development of resentment, and many in the public started accusing certain movies of coming from a fascist point of view. Films like Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs were two of the most vilified, filled with rape, murder, misogyny and misanthropy, both failing to get past the censors in the US with the more marketable R rating. But this could easily be explained away by the fact that both films, despite being made by very famous directors, were produced outside of the studio system and outside of the US. Straw Dogs, which like, A Clockwork Orange was shot in England, was eventually distributed by a smaller company, Cinerama Releasing Corporation, after five minutes of violent and sexual content had been cut out of the film. A Clockwork Orange was made by the secretive Kubrick, and he had complete control over every aspect of his films at that point, even pulling it completely after in England after the negative reaction to its extreme violence.

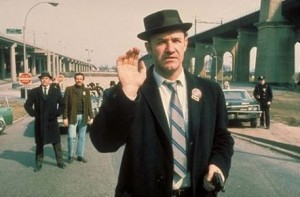

Two other films from 1971 accused of fascism, made inside the studio system and with content less likely to raise ire, were William Friedkin’s The French Connection and Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry. Siegel (The Killers, Hell is For Heroes, Invasion of the Body Snatchers) was an old pro who delivered product on time and under budget and Friedkin, working with a relatively small budget, did not have nearly the control that he would maniacally relish with The Exorcist and every film that followed for the next ten years. More importantly, in terms of their fascism, both films are about racist, reckless cops who are not above murder to get their ultimate goal. A Clockwork Orange and Straw Dogs could explain away their content (movies are people too) by pointing out that they deal with miscreants led astray, just some punks raping and pillaging to get their rocks off. But The French Connection and Dirty Harry come from the inside, employees of the man, showing us how rough it is from their perspective, and how rules and regulations are only there to get in their way and to appease the pansies who complain about wimpy stuff like civil rights.

Two other films from 1971 accused of fascism, made inside the studio system and with content less likely to raise ire, were William Friedkin’s The French Connection and Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry. Siegel (The Killers, Hell is For Heroes, Invasion of the Body Snatchers) was an old pro who delivered product on time and under budget and Friedkin, working with a relatively small budget, did not have nearly the control that he would maniacally relish with The Exorcist and every film that followed for the next ten years. More importantly, in terms of their fascism, both films are about racist, reckless cops who are not above murder to get their ultimate goal. A Clockwork Orange and Straw Dogs could explain away their content (movies are people too) by pointing out that they deal with miscreants led astray, just some punks raping and pillaging to get their rocks off. But The French Connection and Dirty Harry come from the inside, employees of the man, showing us how rough it is from their perspective, and how rules and regulations are only there to get in their way and to appease the pansies who complain about wimpy stuff like civil rights.

Is this how the studios viewed the public, as cattle to be conveniently moved around, lest they go astray and express themselves? The French Connection and Dirty Harry were certainly validated, since the former won five Oscars including Best Picture, and both films spawned multiple sequels, the ultimate endorsement by Hollywood (the public is secondary in these matters).

If Paul Verhoeven had made Dirty Harry in the same vein that he made Starship Troopers, then no one would question the blackly comic satirical intentions mocking the manipulative bloodlust of the media, and certainly not take the movie at face value. Unfortunately, a director less concerned with irony, Don Siegel, made Dirty Harry, and what, with our postmodern glasses on, could play as a sick and twisted cartoon endorsing fascism, actually plays like complete and total sincerity about the evils of the system and how cops should be above the law. This is unmistakable, as the first image of the film gives us a list of policeman who died in the line of duty, and tells us that the movie is dedicated to them. So, what follows is either a cautionary tale about preventing cops from doing their job by handcuffing them with restrictions which will make it likely that they are maimed or killed (Harry is the only one left relatively unscathed at the end of the film, all his partners are either dead or retiring out of fear), or a cautionary tale about handcuffing cops with restrictions, which turns them into “Dirty” Harry.

If Paul Verhoeven had made Dirty Harry in the same vein that he made Starship Troopers, then no one would question the blackly comic satirical intentions mocking the manipulative bloodlust of the media, and certainly not take the movie at face value. Unfortunately, a director less concerned with irony, Don Siegel, made Dirty Harry, and what, with our postmodern glasses on, could play as a sick and twisted cartoon endorsing fascism, actually plays like complete and total sincerity about the evils of the system and how cops should be above the law. This is unmistakable, as the first image of the film gives us a list of policeman who died in the line of duty, and tells us that the movie is dedicated to them. So, what follows is either a cautionary tale about preventing cops from doing their job by handcuffing them with restrictions which will make it likely that they are maimed or killed (Harry is the only one left relatively unscathed at the end of the film, all his partners are either dead or retiring out of fear), or a cautionary tale about handcuffing cops with restrictions, which turns them into “Dirty” Harry.

While it is possible to try to justify Dirty Harry being about what a terrible cop Harry is, the movie is so clearly on his side, every step of the way. Harry’s random dialogue while driving through the evening streets of San Francisco? “These loonies, they ought to throw a net over the whole bunch of ’em.” That sort of statement is an opening to hammer Harry for his close-minded condemnation of the “other,” the response of his partner, the ethnic “sensible” one is a sarcastic-free, “I know what you mean.” Harry’s statement is totally unnecessary anyway, there’s hardly a moment in the film that doesn’t continually remind you that the permissiveness of San Francisco has created this hateful, mindless, manipulative serial killer, named Scorpio, but only tangentially based on the Zodiac Killer. This anonymous, personality-free killer chooses targets that are everything he is not, black, gay, religious, and children, and even though they are mortal enemies, Harry’s sensibility is equally ignorant. The only notion we get about the nameless killer’s background is hinted at by his long hair and pacifist façade when in mortal danger (he’s a hippie, just as bad as them spics and queers!).

While it is possible to try to justify Dirty Harry being about what a terrible cop Harry is, the movie is so clearly on his side, every step of the way. Harry’s random dialogue while driving through the evening streets of San Francisco? “These loonies, they ought to throw a net over the whole bunch of ’em.” That sort of statement is an opening to hammer Harry for his close-minded condemnation of the “other,” the response of his partner, the ethnic “sensible” one is a sarcastic-free, “I know what you mean.” Harry’s statement is totally unnecessary anyway, there’s hardly a moment in the film that doesn’t continually remind you that the permissiveness of San Francisco has created this hateful, mindless, manipulative serial killer, named Scorpio, but only tangentially based on the Zodiac Killer. This anonymous, personality-free killer chooses targets that are everything he is not, black, gay, religious, and children, and even though they are mortal enemies, Harry’s sensibility is equally ignorant. The only notion we get about the nameless killer’s background is hinted at by his long hair and pacifist façade when in mortal danger (he’s a hippie, just as bad as them spics and queers!).

In fact, the deck is stacked so thick that even as Harry is being run around town at Scorpio’s bidding, he is accosted at every turn by muggers, vagrants, or suicidal gay men propositioning sex. What’s funny is that Harry’s interludes feel like padding, there has to be at least 20-25 minutes of screen time dedicated to watching Harry run and it doesn’t really have much to with his catching the killer, the scenes could easily be cut without harm to the film. The only conclusion that can be made is that the filmmakers wanted us to see specifically these acts of violation towards Harry, because we certainly don’t learn anything about him as a person, except that maybe he’s a bit out of shape.

There’s a lot that seems gratuitous in Dirty Harry, from the nudity clearly thrown in to garner an R rating (the movie could have squeaked by with a PG, at least by the lax early 70’s standards), to one of the major plot points, when Scorpio pays a black man, who he race baits, to beat him up so he can blame it on Harry. The beating goes on quite a while, but if it is meant to appear to be a clever ploy by Scorpio to get Harry in trouble, it doesn’t amount to anything. We see Scorpio wheeled in on a gurney talking to the press and blaming Harry for his injuries. Immediately after, Harry is questioned by his superiors about Scorpio’s sustained injuries, and he denies it, and the issue is never brought up again. Even the most blatant example of demonizing the liberal justice system, the scene where Harry is excoriated by the district attorney for shooting and torturing Scorpio so he’ll reveal the whereabouts of the kidnapped girl, doesn’t make much sense. Sure, Harry broke several amendments in his pursuit of Scorpio, and the gun and anything else discovered in his “home” could be justified as fruits of a poisonous tree. But he had just led Harry and his partner on a wild goose chase under the pretense of extortion, but with the intent of murder, beating up Harry and shooting at his partner. After Harry stabs Scorpio in the leg, the only thing that would need to happen would be to match the knife wound with Harry’s knife, which was pulled out and left in the woods by Scorpio and seen by Harry’s superior before he tapes it to his leg (“It’s disgusting that a police officer should know how to use a weapon like that”). This would be corroborated by the testimony of the doctor at the hospital who treated Scorpio and any visual evidence from the shootout above the church or from the helicopter who spotted him on the roof, and Scorpio would likely get life in prison. Not three or four murder convictions perhaps, but anything that happened before the illegal entry into the stadium would be fair game. Is this lazy screenwriting? I’d say it is, partially, but the other factor is that the script was designed with Scorpio getting away on a technicality just so the law can be blamed for its limitations (“well, then the law is wrong”), and so it doesn’t much matter that the specifics have specious logic.

There’s a lot that seems gratuitous in Dirty Harry, from the nudity clearly thrown in to garner an R rating (the movie could have squeaked by with a PG, at least by the lax early 70’s standards), to one of the major plot points, when Scorpio pays a black man, who he race baits, to beat him up so he can blame it on Harry. The beating goes on quite a while, but if it is meant to appear to be a clever ploy by Scorpio to get Harry in trouble, it doesn’t amount to anything. We see Scorpio wheeled in on a gurney talking to the press and blaming Harry for his injuries. Immediately after, Harry is questioned by his superiors about Scorpio’s sustained injuries, and he denies it, and the issue is never brought up again. Even the most blatant example of demonizing the liberal justice system, the scene where Harry is excoriated by the district attorney for shooting and torturing Scorpio so he’ll reveal the whereabouts of the kidnapped girl, doesn’t make much sense. Sure, Harry broke several amendments in his pursuit of Scorpio, and the gun and anything else discovered in his “home” could be justified as fruits of a poisonous tree. But he had just led Harry and his partner on a wild goose chase under the pretense of extortion, but with the intent of murder, beating up Harry and shooting at his partner. After Harry stabs Scorpio in the leg, the only thing that would need to happen would be to match the knife wound with Harry’s knife, which was pulled out and left in the woods by Scorpio and seen by Harry’s superior before he tapes it to his leg (“It’s disgusting that a police officer should know how to use a weapon like that”). This would be corroborated by the testimony of the doctor at the hospital who treated Scorpio and any visual evidence from the shootout above the church or from the helicopter who spotted him on the roof, and Scorpio would likely get life in prison. Not three or four murder convictions perhaps, but anything that happened before the illegal entry into the stadium would be fair game. Is this lazy screenwriting? I’d say it is, partially, but the other factor is that the script was designed with Scorpio getting away on a technicality just so the law can be blamed for its limitations (“well, then the law is wrong”), and so it doesn’t much matter that the specifics have specious logic.

Logic and reality should have been what Don Siegel was going for, and indeed there are some scenes that have a shaky handheld look to them. But then there are others, such as Harry’s rescue of a man attempting suicide, that look exactly like they were shot on a studio backlot. For what is essentially a no-frills police procedural, it is strange that Siegel conceded to such phony footage (budget issues?), as it undermines the specificity of Harry’s story, and, along with the famous scene where Harry interrupts a bank robbery while on his lunch break, moves Dirty Harry into the territory of pure fantasy.

Logic and reality should have been what Don Siegel was going for, and indeed there are some scenes that have a shaky handheld look to them. But then there are others, such as Harry’s rescue of a man attempting suicide, that look exactly like they were shot on a studio backlot. For what is essentially a no-frills police procedural, it is strange that Siegel conceded to such phony footage (budget issues?), as it undermines the specificity of Harry’s story, and, along with the famous scene where Harry interrupts a bank robbery while on his lunch break, moves Dirty Harry into the territory of pure fantasy.

But was the fantasy the point all along? Is Harry’s nihilism and misanthropy part of a larger scheme in which the movie goes so over the top, deliberately, so that any potential message would be immediately dismissed?

William Friedkin went in a totally different direction with The French Connection, opting for a more documentary-style approach, to approximate the grittiness of the NY streets it was made on. Indeed, this comes in handy with a lot of the morning exterior photography, which really captures the city perfectly, nailing down that bleary-eyed emptiness of the streets before 6 am. Friedkin’s attempt to be realistic goes so far that there’s actually very little action in the movie, at least half the film has its main characters, nicknamed Popeye and Cloudy and played by Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider, sitting either in their cars or in an empty apartment on stakeouts.

William Friedkin went in a totally different direction with The French Connection, opting for a more documentary-style approach, to approximate the grittiness of the NY streets it was made on. Indeed, this comes in handy with a lot of the morning exterior photography, which really captures the city perfectly, nailing down that bleary-eyed emptiness of the streets before 6 am. Friedkin’s attempt to be realistic goes so far that there’s actually very little action in the movie, at least half the film has its main characters, nicknamed Popeye and Cloudy and played by Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider, sitting either in their cars or in an empty apartment on stakeouts.

Friedkin’s strategy was to play with these silent moments by lulling you into a false sense of calm and security. He opens with blaring, discordant, and unpleasant orchestral music over the credits. There’s nothing to look at, just the names of the cast and crew over a black screen as the music screeches. Then he goes to back to quiet for five or six minutes, before there’s an out-of-nowhere shooting, that is certainly a surprise, but if you think about, rather extraneous to anything that follows. It certainly helps the pacing with this stop-start mentality, The French Connection is glacially slow and dull by modern standards, and the best way to deal with that is to keep us on edge, never knowing when the next burst of violence will come from.

That’s the only possible explanation for why he has Popeye throwing out racial epithets whenever he can, to keep your nerve of angst and hate up, it doesn’t seem inherent to the character, who is mostly a hapless, drunk loser. When we see his apartment, by then we’ve already spent enough time with him to find him uncouth, and so its messiness isn’t a surprise, but the fact that he has a one-night stand with a young, attractive and apparently kinky girl (she handcuffs him to the bed using his own cuffs) is wholly unbelievable. The previous scene showed Popeye waking up in a bar, and nursing his hangover with more liquor, he was in no condition to find any woman, and he simply doesn’t have the charm regardless of his level of inebriation. Really, his sexual conquest should have been played as a joke, but Friedkin has no sense of humor that he is aware of, and so The French Connection is without any respite or sidetrack with a joke.

That’s the only possible explanation for why he has Popeye throwing out racial epithets whenever he can, to keep your nerve of angst and hate up, it doesn’t seem inherent to the character, who is mostly a hapless, drunk loser. When we see his apartment, by then we’ve already spent enough time with him to find him uncouth, and so its messiness isn’t a surprise, but the fact that he has a one-night stand with a young, attractive and apparently kinky girl (she handcuffs him to the bed using his own cuffs) is wholly unbelievable. The previous scene showed Popeye waking up in a bar, and nursing his hangover with more liquor, he was in no condition to find any woman, and he simply doesn’t have the charm regardless of his level of inebriation. Really, his sexual conquest should have been played as a joke, but Friedkin has no sense of humor that he is aware of, and so The French Connection is without any respite or sidetrack with a joke.

Even the standard low level of humor that is almost a necessity in a cop film, Friedkin turns into political commentary. As Popeye stands on the corner, watching Fernando Rey, the smooth French drug dealer he is after, from across the street in the cold, we see Rey in a restaurant being served the most expensive and elegant food while Popeye stands, freezing for hours while he gets picks his nose, eats cold pizza, and drinks terrible coffee. The juxtaposition goes on long past making the point of showing how the criminals live well while our protectors suffer, and eventually becomes an issue of voyeurism. Since Friedkin has Popeye and Cloudy constantly tailing Rey, not just looking at him through restaurant windows, but in store window reflections (the movie shows how cheap the characters are, they can’t stop window shopping), through subway cars, and any other possible way to stare at someone from just enough distance where they sense you but can’t see you.

All that sounds like constant repetition but the neverending waiting and watching seem to be what Popeye and Cloudy like most about the job, the only pleasure we see them take is when they are listening in on a wiretapped phone. The French Connection is so procedural, there’s even a lengthy lesson on how to take apart a car, piece by piece, that its languorous nature just reinforces how dull police work must be. The famous car chase through uptown Manhattan is one of the few scenes that feature any real interactivity with the public, and that’s just so Popeye can commandeer a car. Even that scene ends with Popeye unnecessarily shooting the suspect in the back, the movie works really hard at trying to make us find him disreputable, but all it does is remove us emotionally, since we can’t really figure out whose side we’re supposed to be on. Much like Dirty Harry, there’s the suggestion that, in these filthy city cesspools, it is impossible to tell the criminals and citizens apart, which is one of the few times that The French Connection gives us any notion of its fascist intentions. There’s a totally gratuitous scene where Popeye and Cloudy toss a bar, and every single one of the [black] patrons is carrying drugs, and rather large amounts for just personal use. How could they all be drug dealers? There’s a strange disconnect that based on this raid, Popeye pitches his chief on the sting operation because there has to be a big shipment coming in, since no one is carrying, and they’ll need a fix soon. Perhaps Friedkin thought that the scene was either implausible or boring, because the next time he tries to convince his chief of anything, the exposition occurs amidst a gruesome traffic accident, with a lot of gory close-ups, none of which have to do with the story at all, it was just a distraction by way of shock and gross-out. That appears to be Friedkin’s entire strategy, smash cut sound transitions interspersed with cops falling asleep while their partner watches an empty car on the street (if the movie is remade, an appropriate title might be Loud, Quiet, Loud).

All that sounds like constant repetition but the neverending waiting and watching seem to be what Popeye and Cloudy like most about the job, the only pleasure we see them take is when they are listening in on a wiretapped phone. The French Connection is so procedural, there’s even a lengthy lesson on how to take apart a car, piece by piece, that its languorous nature just reinforces how dull police work must be. The famous car chase through uptown Manhattan is one of the few scenes that feature any real interactivity with the public, and that’s just so Popeye can commandeer a car. Even that scene ends with Popeye unnecessarily shooting the suspect in the back, the movie works really hard at trying to make us find him disreputable, but all it does is remove us emotionally, since we can’t really figure out whose side we’re supposed to be on. Much like Dirty Harry, there’s the suggestion that, in these filthy city cesspools, it is impossible to tell the criminals and citizens apart, which is one of the few times that The French Connection gives us any notion of its fascist intentions. There’s a totally gratuitous scene where Popeye and Cloudy toss a bar, and every single one of the [black] patrons is carrying drugs, and rather large amounts for just personal use. How could they all be drug dealers? There’s a strange disconnect that based on this raid, Popeye pitches his chief on the sting operation because there has to be a big shipment coming in, since no one is carrying, and they’ll need a fix soon. Perhaps Friedkin thought that the scene was either implausible or boring, because the next time he tries to convince his chief of anything, the exposition occurs amidst a gruesome traffic accident, with a lot of gory close-ups, none of which have to do with the story at all, it was just a distraction by way of shock and gross-out. That appears to be Friedkin’s entire strategy, smash cut sound transitions interspersed with cops falling asleep while their partner watches an empty car on the street (if the movie is remade, an appropriate title might be Loud, Quiet, Loud).

So is The French Connection fascist? No, I don’t think it is. Popeye is not very good at his job and rather careless, despite how much in common he might have with Dirty Harry with regards to how much he trusts his hunches, and it doesn’t appear that the system really gets in the way of his work. That is, until the totally disingenuous closing crawl, with still images telling us what happened to the criminals. The point is made, they can hide behind the law and get light sentences or get off completely free, and only the most innocent of them gets a rough deal (the actor, who they used as a patsy). Harry is reckless as well, but he gets his man, despite the red commies in the DA’s office, and Popeye is rather hapless, but his effort was fruitless anyway. The closing bits of information in The French Connection nullify the effectiveness of the concluding scene, and certainly make the movie itself rather pointless. At least Dirty Harry is consistent with how appalling it is.

So is The French Connection fascist? No, I don’t think it is. Popeye is not very good at his job and rather careless, despite how much in common he might have with Dirty Harry with regards to how much he trusts his hunches, and it doesn’t appear that the system really gets in the way of his work. That is, until the totally disingenuous closing crawl, with still images telling us what happened to the criminals. The point is made, they can hide behind the law and get light sentences or get off completely free, and only the most innocent of them gets a rough deal (the actor, who they used as a patsy). Harry is reckless as well, but he gets his man, despite the red commies in the DA’s office, and Popeye is rather hapless, but his effort was fruitless anyway. The closing bits of information in The French Connection nullify the effectiveness of the concluding scene, and certainly make the movie itself rather pointless. At least Dirty Harry is consistent with how appalling it is.