A very long interview with Outrage director Kirby Dick. It’s long. Take a lunch break so you can finish it.

Obligatory photo of subject of interview.

Along with allowing us to see his documentary Outrage, about outing closeted gay politicians who vote against their own interests (I’ve reviewed the movie here), director Kirby Dick was kind enough to go on a press tour. There were 4 reporters in the room, 3 if you don’t count me. Since I was not able to ask all the questions I would have liked, occasionally, what I was thinking came out of the mouth of another reporter, and I will detail that below. Also, the entire interview, which ran for 35 minutes, has been edited to remove questions that do not mirror my clearly biased agenda.

Not Me: Are you surprised with how quickly the controversy is coming, following Outrage‘s premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival?

Kirby Dick: You know, I guess I’m not that surprised. I’m in some ways I, to some degree, welcome a certain amount of discussion around this issue. In part because I think this is an unreported story and underdiscussed issue and if people disagree with aspects of the film or disagree with outing I would rather the discussion be happening in sort of a more public arena. The closet exists because it is not being reported on and what happens is young politicians when they are choosing a political career, before they are even elected to a office – often in their late teens or early 20s – historically they made a decision to go into the closet often because they think this is just not an issue that the press is going to cover that extensively. That is one of the things I am hopeful that the discussion around my film will influence the decisions these politicians make and I think the right decision and I hope they will come to decision is that the right decision for them personally and politically is to run as an out candidate and I think as a result of that hopefully one of the things I hope this film will do is to cause the demise, or the partial demise of the closet so that it will no longer be a major factor in American politics.

Not Me: What was your biggest surprise in making this film?

KD: Initially I was surprised like everyone else was at how gay DC was. I was surprised there are perhaps as many, perhaps more, gay Republicans than there are Democrats. It seems like an oxymoron, but from within the world of DC it makes a lot of sense. I was surprised that there were as many closeted politicians and you know, I as a filmmaker, I tend to often in maybe a quicker – well I don’t know if quicker – getting into a subject is these levels of realizations that I realize if I am going through a number of them like this this is kind of interesting material to be working on as a filmmaker.

Not Me: How did you decide to come upon this as a film?

Not Me: How did you decide to come upon this as a film?

KD: Well I was in Washington, DC and I was promoting This Film is Not Yet Rated, which is about the censorship in the American films rating system. I only knew about that subject matter because primarily I worked in the film business. I thought, well here I am in DC, there is probably a number of great subjects for documentaries that people primarily within Washington know about and others don’t. So I started asking around and I quickly came on the subject matter

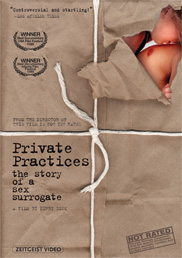

My question: What got you started in a broader appeal? I watched some of your documentaries before this one, such as Sick: The Life and Death of Bob Flanagan Supermasochist and Private Practices: The Story of a Sex Surrogate, and they are very specific, and Outrage and This Film is Not Yet Rated are a little broader and a little wider view, not so much focused on specific people.

KD: I think the shift happened at Twist of Faith, the film about clergy sexual abuse that was nominated for an academy award. That was kind of a crossover film in that it was very personal; there was a lot of verite. It was focusing on primarily the psychological experience of one subject. But it was about a real societal wrong, particularly what the Catholic Church was doing and particular in Toledo the Toledo diocese. It was after that film that I realized that I had this opportunity to step into the public sphere and make people aware of things. When I was In the beginning of my career I just didn’t have the expertise even to work in that arena quite so effectively. So I have made a conscious choice to work in a more political vein, but I always like the psychological element if I can find it.

Governor Charlie Crist shows his true color.

Not Me: When going up against people in DC, there must have been a lot of resistance. What techniques were used to get people to talk?

KD: Well my producer Amy Ziering was the person who contacted most of these people first. She is just very persuasive, very skilled and I think at conveying the intent of the project which was anything but tabloid. It was meant to be a deep exploration of this. I think it was that approach which was very effective because most of the people – all of the people on my film – whether they’re Democrat or Republican wanted this story told. They had lived in the closet – many of them had lived in the closet, all of them knew people in the closet so all of them knew the personal damage of the closet. Nearly all of them had witnessed fairly intimately the political damage of people in the closet choosing to vote anti-gay to protect the closet as a result harming millions of Americans. They felt if the story was told, again the closet might diminish and things would improve in this country. So they wanted it told. The challenge was that DC is a very buttoned down town and everybody needs to be very careful. But, step by step.

Not Me: Where do you think this comes from, psychologically?

KD: That’s a good question. Sometimes I just think it’s pragmatic. I think some of these politicians accept themselves and have made the decision that I am going to have gay relationships but I am publicly going to be anti-gay. If they see that is the way they can have a sex life at the same time, what they perceive is the only way to have a career. I should say I feel a great deal of empathy for these politicians because in spite of often times their horrible voting record they are victims themselves of homophobia. I don’t think that should be overlooked. I think there are some for whom it is such a, they are brought up – it’s not in the film, but Michelangelo Signorile, we almost put it in, it was like a minute clip and was just too long. He is sort of like the elder statesman of this whole thing. But he made this observation that somebody is brought up in a Republican family, this sort of golden child that is being targeted for political office. This is one thing you see. It happens over and over and over. People get picked and they just get dragged right in. Isn’t that sweet? There is only problem that they find out in their teens they’re gay. They will do everything they can do deny it or just maybe isolate it. That is when the psychological tension begins to develop, especially if their family is fundamentalists in anyway, then the problem is compounded.

I was thinking this, but didn’t get to ask it: What did you cut out for legal reasons?

KD: It was more journalistic than legal, that was the issue. It was really, there are rumors about a number of other politicians in national politics and in DC.

Not me: Who was the one you came closest to? Was it Karl Rove?

Not me: Who was the one you came closest to? Was it Karl Rove?

KD: No, I mean I myself did not come across and substantiation that he is gay. I’ve heard the rumors. But there were others that where there was some substantiation it just wasn’t enough. It was really important to me, the way this subject matter has been dealt with – not so much by the press and not by Mike Rogers – but by some in the blogosphere is the rumors. There is something sensational. Okay, that is fine. That is a form of reporting. Reporting rumors, that is fine. For this film, because I really wanted this film to be taken seriously, I thought that would diminish its impact. It would certainly make it maybe more enjoyable to watch. But I wanted to be really careful with the way I was presenting it was accurate.

Not Mine: Your last film dealt with secrecy within Hollywood and Hollywood is known for having many in the closet. Did you see the parallels between the two worlds?

KD: I did and we discussed including that in the film. The problem was it was like trying to get two subjects into one subject. They are related but they are also separate. We actually tried to sort of get it in passing and then suddenly it was like this whole issue and it is an even more controversial issue. Then it’s not getting addressed. There is a strong argument to be made. I don’t necessarily know where I stand on this. But there is a strong argument to be made that an A-list star is even more powerful than someone like Larry Craig, he is even more influential. If he chose to come out it might affect the cause of gay rights more than if Larry Craig came out and voted 100% pro-gay. But we chose to draw the bright line on elected officials who actually have political power over others and are voting hypocritically. That was our bright line and there was a reason. One of the reasons I did that, one of the most important reason is I think the discussion around outing, while important, has often obscured the more important underlying issues. I wanted to make the film because I wanted the discussion to happen, but more importantly I wanted to make the film to get past that.

Not me: So maybe the sequel we’ll see that?

KD: [laughs] Another filmmaker. I’m off of this subject matter for awhile.

Charlie Crist and Mark Foley discuss the romantic entaglements possible while using instant messenger.

Me: Did you meet any ex-gay politicians?

KD: No, I didn’t. That was another thing we considered going into but didn’t.

Not Me: What drew you to Outrage – was it the topic or the timing?

KD: I think it was more around the political climate around in August 2006 it looked like the anti-gay agenda, anti- gay hysteria was going to continue. The Republican Party was going to be able to effectively continue to use this. As a filmmaker I wanted to somehow put a stop to that. Not to necessarily, I don’t view this as a particularly partisan film. I just think it is so wrong for a party or an administration to advance its own political ends at the expense of a portion of its citizens. I just felt this was just a way that I could enter the debate.

Not Me: One of the title cards at the end of the film suggests that Charlie Crist is a leading candidate for 2012 for the Republican Party. Do you think he could withstand the homophobia of the Republican Party?

KD: It’s not about, this is not a film that was made to in any way damage his career at all. I don’t really take a particular position on Charlie Crist, other than the issues that are around gay rights. You know, he is a very middle of the road candidate, a very popular candidate, obviously a very skilled politician. I’m certain it will have an impact. I mean personally a greater impact was his decision to get married because it closed the door you know, who knows. He is a young politician. There is nothing to say 2016, 2020 he couldn’t run.

Not Me: Try to have a few children?

KD: Or come out. I mean three years ago the idea of an African American winning the presidency was an opened question. Now a skilled politician like Obama comes along and the right political climate and it’s like oh, well of course. That could happen in 8 years. Could you imagine if Crist, even now I think in some ways – it’s trickier now that he has gotten married because that raises all these other issues.

Not Me: Like hypocrisy?

KD: Well, not only hypocrisy, but the problem is the institute of marriage has been defiled by –. But what if he wasn’t married and he just said look, I’m going to come out and tell the truth. Regardless of what my political career is, what my political future is. First of all he would be deified. I mean he wouldn’t be Martin Luther King, but the amount of respect to be gained from that.

Charlie Crist waves goodbye to the only person who thought his marriage was real.

Not Me: But how do you reconcile that with the radical shift by the Republican Party?

KD: I am not saying it’s probable. But politics and the political climate has a way of surprising us. Right now, even the Republican Party is struggling with should this be an issue at all. I can see the Republican Party, I mean they have other issues. Maybe they will go back to something else. There is no question if the Republican Party stopped attacking gays they would probably get at least another 10% of the gay population in their camp again. That is a powerful and very wealthy constituency. That could make some difference in where they want to go. Let’s just hope…I’m just rambling.

Not Me: The film does a good job of balancing Republican and Democrat, Gay and Lesbian. Was that a conscious effort to be impartial? Is that something you set out to do?

KD: No, I didn’t want the film to be partisan. I tend to vote Democratic. I am registered as a Democrat, but I have a great deal of criticism for the Democrats in many, many ways. I think the two party system is hugely problematic in this country. I wish, we wanted to address, we did have Mary Cheney, but I actually feel that – I would have liked to have one other subject who was lesbian to focus on.

Me: Have you ever suffered producer interference with your documentaries? I was watching I Am Not A Freak! (a made-for-TV documentary about people with major physical disfigurements that Dick made early in his career) today and if there was ever anything that really seemed like a producer got in the way, with the Orson Welles-style narration, the really weird opening crawl that seemed to defeat the purpose of the entire movie.

KD: What was it?

Me: It was like watching Cruising, one of those warnings where it says something to the effect of “this may disturb you, but these are real people.”

Me: It was like watching Cruising, one of those warnings where it says something to the effect of “this may disturb you, but these are real people.”

KD: [laughs] I’m not sure I’m responsible for that.

Me: Well there’s even stock footage of a guy you clearly didn’t interview, the guy with the second head (Chang).

KD: [laughs] I’m sure there was some. I guess I have to take responsibility. That’s a cult film. It’s weird, not that I’m defending it but it’s surprising how you make these things and they come back to haunt you many years later. Not especially. I have on one film, which I don’t actually want to identify, but there was some interference. But for the most part, no. for the most part, these films are my films and they rise and fall on my decision and probably mostly on that one as well.

Me: I was listening to the commentary on Private Practices and that guy wouldn’t shut up, the guy next to you. And he was asking the most inane questions. I couldn’t believe how calm you were. I thought to myself, “he must be about 12 years old.” And then he said he was the producer of Outrage. He must have interfered the whole time.

KD: [laughs] I’m glad we’re talking about this. He’s actually a very good friend. The idea was, you know you do these commentaries and you get so stiff – maybe I should do it like this you know because you get so stiff. You can’t even remember, nobody is throwing, you don’t throw yourself the provocative questions.

Me: He was asking infantile questions though. It’s a serious subject matter and he just keeps asking “Is she a whore?” over and over.

KD: He’s actually a very interesting fella. He’s making a very interesting film.

Me: But he’s older than 12?

He’s older than 12. He looks 12 though… He was very helpful. The co-producer is not the same thing as Amy Ziering, but anyway.

Not Me: What is it about specifically about the documentary genre that resonates with you?

Not Me: What is it about specifically about the documentary genre that resonates with you?

KD: I think it is an extremely wide open genre. You can pretty much do anything and call it a documentary and it will be a documentary. That one of the things I like about art, there is kind of a wide open territory if you will. I don’t think it’s being explored as rigorously as it could be. I don’t think film critics in general understand how films are made. I think film critics are brought up understanding how dramatic films are made, but I think documentaries are a bit of a mystery. Often times, the criticism – not in terms of whether they are bad, I think they are very capable of making judgment about them, but how exactly the films are made is sometimes a mystery to them. What do I like about documentary? I like the filmmaker’s subject relationship. Issues of voyeurism are currently at play, whether it’s shooting, performance, projecting you know the projection of the relationship between the audience. Voyeurism is always at play there. The issues of truth, bring that into question. Now in this political climate I think documentaries have a role to play particularly in the demise of many investigative reporting departments. In newspapers, that is horrible for the country but that is great for documentary filmmakers. Finally in terms of the rise of documentaries in this country a lot of credit goes to George W. Bush. He angered the documentary community is of course more liberal than conservative and it just really angered people.. They saw that there was not enough critique of that by the mainstream press and they felt compelled to step in.

Not Me, but I was about to ask this: Does the notion of making a non-documentary hold any interest to you?

Vincent D'Onofrio in Guy

KD: I did write a film that was produced that which was called Guy, starring Vincent D’onfrio and Hope Davis. I don’t know if you can get it. It was actually quite a good film. Back in 1996 it played at Venice. It apparently got deep-sixed by somebody within, it was Polygram at the time which was subsequently acquired by Universal. But I think it was deep-sixed by an exec in there. But it dealt with documentary filmmakers. It was about a woman who followed a man around with a video camera. She was somewhere between kind of a performance artist, stalker, documentary filmmaker. It was all about all kinds of issues, but certainly one was about documentary subject relationships. I personally feel, while there are a lot of wonderful dramatic films being made, maybe I am going out on a limb here, the medium of dramatic filmmaking is in decline. I really going to go out on a limb here and I think a lot of the energy is getting sucked into the internet. I think documentary, look at Youtube, it’s still alive on the internet. And of course, to some degree, dramatic filmmaking. I suspect, and I’m sort of guessing here, you are going to see, I think you are going to see and maybe already seeing dramatic filmmaking being — I have two children, one is 22 and one is 19. They are different but going to a high school my daughter would see many films. My son it just wasn’t an issue. It was just a complete change, so it’s one example, but we’ll see.

Me: Were you ever scared off by what [Oscar winning documentarian] Errol Morris had to deal with on The Dark Wind. He made his one [fiction] movie, and then Robert Redford took it away from him and mangled it. And Morris went back to documentaries after that. Is that like a cautionary tale for you?

KD: No, but I’ll tell you something. People don’t screw with you as much when you are making documentary. They don’t know what you are doing and sometimes you don’t either. Sometimes it’s deliberate actually. I actually don’t write my own scripts. I don’t write a script for documentary. I like to dive into a subject and have it go in all directions and sort of scramble to put it together. It seems like every time I am at a point I am making a film I am going this film is going to fail I have to accept it. Then it somehow kicks me in the ass and I go well, I can’t just let it fail. I have to really pursue it to the end and then let it will fail. And that additional kick helps. I use that with people I am working with like you know, you can’t let this thing fail. You gotta work hard. I’m working hard today. But there is something about having control, people don’t mess with you as much when you are making a documentary. I know the craft now. I think it is something that you can really enter the cultural debate with documentaries.

Famed documentarian Frederick Wiseman

Me: I was thinking you are somewhere between Michael Moore who writes a script for his documentaries and Frederick Wiseman, who picks a subject and then just shows up and shoots, knowing nothing about the subject matter beforehand, and finds the movie in the editing room. Do you do a lot of research before hand?

KD: I do a lot of research before and I continue all the way through the end. No I am not Frederick Weisman. Even my verite films, I guess — although I never worked with him so I don’t know how purely fire to the wall he is, I mean that is a myth in itself. Not to say he is propagating it. He may be very extreme in that direction I don’t know. There is the amount of back and forth that goes on between filmmaker and subject, even in his films I’m sure is significant.

Not Me: With the fall of newspapers, it seems you’ve taken on the role of an investigative reporter.

KD: It’s taken that role of investigative reporting because its been left open to fill. I mean the field has been left open to documentaries because a number of these subjects that documentary films are covering, if the investigative reporting departments were fully staffed the reporters would have gotten there first. I think a lot of stories are getting completely lost as a result of this change in journalism.

Not Me: Did you catch any of the anti-gay marriage commercials that have been playing recently?

KD: I haven’t it. How do they compare to the ones that are going on in Florida?

Me: They are ridiculous and are unintentionally funny.

KD: I would never assume that any fight for human rights is ever over. I mean first of all, things hang in the balance right now. Proposition 8 will probably be upheld, that is the conventional thinking right now in California. That might change. I think they are getting pressure from Iowa, the Iowa decision, the California Supreme court. That could be there for 20 years. Who knows what could happen in 20 years. And I mean it takes one more terrorist attack and you know some politician could rise up and they could chose=2 0this as an issue.

Not Me: Did you have any trepidation in making this film?

KD: Well, you know it’s a bit risky on my part. But I have sort of taken the attitude that I am going to take my risks until I encounter something that I genuinely have to be afraid of. And then at that point I am going re-evaluate whether or not I am going to proceed because there are so many times when people would say to me that is a great risk. I didn’t want to be in a position of restricting myself from not knowing that. Often times its fear that keeps people from speaking out, doing the research and I wanted to take the risk.

Not Me: From making this film, do you have any additional insight to women who serve as their beards. What makes them tick, is this just deep denial or something else?

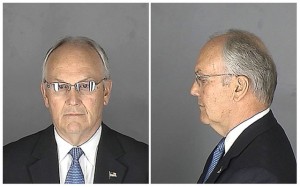

Larry Craig poses for Annie Leibowitz

KD: I think for people who, I don’t know for a fact that Larry Craig’s wife is aware of this. I personally think she is, but I don’t know that for a fact. But you know there is a lot to benefit to be gained from someone in her position to be the wife of a senator. This has gone on through history, recent history anyway.

Not Me: Was there any interest in trying to get a comment from Larry Craig or Charlie Crist?

KD: Well, I think that what we decided was for nearly all the subjects that politicians we focus on, they have already been asked that question; whether they are gay or not really is the central question here. Their answer has been included in the film usually in the form of clips. Whether it is a denial or an evasion, so we felt that was giving ample opportunity. We also feel that you know these are powerful people, they can always speak out if they choose to.

And then I asked one last question which was on a totally different subject, so if you’ve read this far, congratulations, you only have one paragraph to go.

Me: When watching This Film Is Not Yet Rated, you found out who the [MPAA members] were, but did you ever get a chance to interview them? Because at the end we’re stuck with these people who are sort of anonymous, and I thought you were going to go interview them.

KD: I thought that would make them very uncomfortable. Perhaps I could have. I mean these weren’t public officials, I could have as a journalist. I’d sort of made my point. We would have found out that these were just regular people without the qualifications to be in that position.