To Live and Die in LA

Here’s the idea behind “An American, a Canadian, and an Elitist”: Rhett’s favorite movie is “Meatballs 4”, Josh likes Hollywood pap, and Adam is a prick who hates everything. We all watch far too many movies, and spend our time analyzing them. So we each watch the same movie, write our analysis of them, and then go to a chat room to discuss it, unaware of what the others have written. A warning: if you haven’t seen the film we are discussing, it may not be best to read this article, because it is spoiler heavy.

If there is anything to be said about William Friedkin, it is that he is a man who destroys all expectations. You are never safe in his world. Just when you think Popeye Doyle has his man in The French Connection, all Friedkin gives you are a couple gunshots and empty hands. The Exorcist went into excess never explored before, and just when you thought it was over he would throw in a head twist. In what was marketed as a mainstream Pacino thriller, Cruising became a surreal foray into a homosexual world, accented in the final shot with a sexual ambiguity that never happens in Hollywood film, not before or since. Friedkin’s 1985 return to gritty cop territory, To Live And Die In L.A. is an entire play on expectations. All the twists and turns come together though, in a film that feels the most complete and satisfying of Friedkin’s entire body of work. The final twist is less anti-climactic and thematically more suitable than the one in The French Connection, while the extreme blood and violence gives L.A. a gritty realism, compared to the needless excess of the vomiting and offensiveness of The Exorcist. Friedkin walks a fine line with this film, and he succeeds brilliantly. This is a film that critics have dismissed and forgotten, but today we are here to remember.

The pre-title sequence is a quick action exploit, having the star, William Petersen and his partner, Dean Stockwell, capturing and disposing of a quick terrorist. The scene seems to exist for only two reasons: 1. To start the film off with a burst of action, a requisite these days. 2. To allow Stockwell to utter the most cliche line in the history of cop films: “I’m too old for this shit.” This scene hammers home the cop movie cliches precisely so Friedkin can break them in the next scene and continue to do so for the rest of the 100 minutes of film to follow. The next scene has Petersen, looking alone and depressed, wavering on the edge of a bridge, seemingly contemplating suicide. He jumps, and he falls, and only later do we realize that he is tied in with a bungee cord. This establishes Petersen as the typical wildcard cop, but the way Friedkin conceals the bungee cord payoff, it gives us an air of uncertainty towards his character, and towards the punches that Friedkin is going to pull in this film. What at first seemed cliche with the “I’m too old for this shit” self-assessment immediately becomes something apart from the norm. Friedkin jumps on a freefall with no net of formula to catch him.

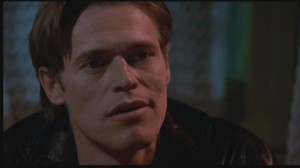

There is one truly great red herring that shows that Friedkin is completely confident with himself and his film that he is willing to flush expectation down the toilet. After bad guy Willem Dafoe watches an interpretive play, he goes back stage to meet one of the performers. With a crew cut and a masculine painted face, the performer moves in and kisses Dafoe. The instant connotations of this shot suggest that Friedkin is going to attribute villainy to homosexuality, like many of his detractors accused him of doing with his previous films. People picketed Cruising for presenting gay sub-culture as a cesspool of filth and sin and for making the lead antagonist a blatant homosexual. Cruising nearly destroyed Friedkin’s career, and he entertains the notion that he again is going to explore homosexuality from a negative perspective with L.A. Then, with a witty touch, the performer reveals the crew cut as a wig, allowing her curly feminine hair to run free. With that scene, Friedkin destroys anyone’s preconceived notions about the film and about his concerns as a filmmaker. He daringly refers to the film that almost destroyed him in order to show that all the bets are off with this film, that this is a different film than Cruising and also one that will not cater to expectations.

There is one truly great red herring that shows that Friedkin is completely confident with himself and his film that he is willing to flush expectation down the toilet. After bad guy Willem Dafoe watches an interpretive play, he goes back stage to meet one of the performers. With a crew cut and a masculine painted face, the performer moves in and kisses Dafoe. The instant connotations of this shot suggest that Friedkin is going to attribute villainy to homosexuality, like many of his detractors accused him of doing with his previous films. People picketed Cruising for presenting gay sub-culture as a cesspool of filth and sin and for making the lead antagonist a blatant homosexual. Cruising nearly destroyed Friedkin’s career, and he entertains the notion that he again is going to explore homosexuality from a negative perspective with L.A. Then, with a witty touch, the performer reveals the crew cut as a wig, allowing her curly feminine hair to run free. With that scene, Friedkin destroys anyone’s preconceived notions about the film and about his concerns as a filmmaker. He daringly refers to the film that almost destroyed him in order to show that all the bets are off with this film, that this is a different film than Cruising and also one that will not cater to expectations.

A full frontal nudity shot of William Petersen quells any doubt that this film is not going to play by mainstream conventions, but it is with the ending that the film comes to full synthesis. In the final confrontation between Petersen and Dafoe, Petersen is shot in the face and killed instantly. This scene again bucks the expectations of a cop film, but it also seems paradoxically the most realistic. Almost every crime thriller is a total “cop” out, because it presents the renegade protagonist as one that is seemingly invincible. Mel Gibson’s Martin Riggs jumps off of moving vehicles, drives his car into the 5th story window of a high-rise only to emerge out the back window, and is able to remain suspended underwater for 5 conscious minutes in the Lethal Weapon films. Will Smith and Martin Lawrence escape plenty an explosion, dodge millions of bullets and nearly destroy an entire freeway in the Bad Boys films. Yet, all these characters, no matter how dangerous the situation, always emerge unscathed and ready for the sequel. Reality would have them killed within 10 minutes of their respective films.

A full frontal nudity shot of William Petersen quells any doubt that this film is not going to play by mainstream conventions, but it is with the ending that the film comes to full synthesis. In the final confrontation between Petersen and Dafoe, Petersen is shot in the face and killed instantly. This scene again bucks the expectations of a cop film, but it also seems paradoxically the most realistic. Almost every crime thriller is a total “cop” out, because it presents the renegade protagonist as one that is seemingly invincible. Mel Gibson’s Martin Riggs jumps off of moving vehicles, drives his car into the 5th story window of a high-rise only to emerge out the back window, and is able to remain suspended underwater for 5 conscious minutes in the Lethal Weapon films. Will Smith and Martin Lawrence escape plenty an explosion, dodge millions of bullets and nearly destroy an entire freeway in the Bad Boys films. Yet, all these characters, no matter how dangerous the situation, always emerge unscathed and ready for the sequel. Reality would have them killed within 10 minutes of their respective films.

There are only so many bullets one can dodge before a scene becomes entirely unrealistic, and that is the flaw of so many cop films. To Live And Die In L.A. take the bold step of killing off the main character, and that conclusion seems so fitting. Petersen was a guy living on the edge, and it was inevitable that eventually he would succumb to the same fate of his deceased partner. By killing off Petersen, Friedkin creates an ending that is true to the main character, rather than true to the conventions of the cop genre. Friedkin zeroes in on the essence of Petersen’s character, he was a man with a death wish, and that is just what fate dealt him.

With Petersen gone and dead, Friedkin allows the film to explore a theme that permeates many of his works. Petersen’s replacement partner, John, is left without a partner, and in order to deal with his grief and uncertainty, he assumes Petersen’s entire persona: taking control of his woman, talking with authority and moving with confidence. The concept of taking up another’s personality and beliefs is one that Friedkin dealt with considerably in Cruising. In the conclusion to that film it is suggested that Al Pacino transforms into the killer he was hunting. So engulfed in homosexual society, Pacino assumes a gay outlook in order to cope with death he caused. Likewise, John morphs himself into Petersen in order to avoid the guilt of seeing his partner shot. It is a fascinating concept, and by returning to Cruising (and this time committing, unlike the aforementioned gay tease) Friedkin demonstrates his backbone the most. He explores a recurring preoccupation that he entertained in Cruising and takes it a step further in L.A. despite all the negativity that referencing Cruising would bring to his film. Friedkin is making his movies for the art, not the glory of critical reception or box office receipts.

With Petersen gone and dead, Friedkin allows the film to explore a theme that permeates many of his works. Petersen’s replacement partner, John, is left without a partner, and in order to deal with his grief and uncertainty, he assumes Petersen’s entire persona: taking control of his woman, talking with authority and moving with confidence. The concept of taking up another’s personality and beliefs is one that Friedkin dealt with considerably in Cruising. In the conclusion to that film it is suggested that Al Pacino transforms into the killer he was hunting. So engulfed in homosexual society, Pacino assumes a gay outlook in order to cope with death he caused. Likewise, John morphs himself into Petersen in order to avoid the guilt of seeing his partner shot. It is a fascinating concept, and by returning to Cruising (and this time committing, unlike the aforementioned gay tease) Friedkin demonstrates his backbone the most. He explores a recurring preoccupation that he entertained in Cruising and takes it a step further in L.A. despite all the negativity that referencing Cruising would bring to his film. Friedkin is making his movies for the art, not the glory of critical reception or box office receipts.

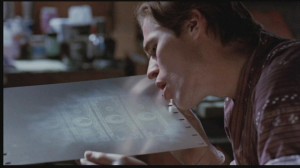

Knowing the risks Friedkin took with To Live And Die In L.A., you can read the Dafoe character as a parallel to himself. Dafoe mass produces capitalism in the form of counterfeit bills, just as many would consider Friedkin to be making motion pictures to fuel American capitalism. Dafoe however, is an artist before he is a counterfeiter, surrounded by his own expressive paintings. More than just literally making money, Dafoe is doing it as a means of artistic expression. The same can be said for William Friedkin. The key thing to note is that Dafoe makes his paintings as a form of artistic release. After he paints them, he burns them. Dafoe does not care about fame or glory, only about expressing the notions that he keeps suppressed within. Similarly, Friedkin makes his pictures the way he wants to, content only with getting his intended vision on the screen. The DVD of L.A. shows the ending that the financiers tried to impose on the film to make it more commercial. Friedkin vehemently rejected it, and his film was a box office bomb. It is a fascinating piece of art however, and unlike Dafoe’s paintings, it remains with us forever to appreciate.

Some time ago my good friend and filmmaking cohort Mani produced a mock trailer called Pigs in a Blanket for a class. It ran two minutes and thirty seconds and was an outrageous clusterfuck of all possible cop movie cliches. One cop is bad, the other is worse. They get on each other’s nerves and their relationship is volatile. They rough up suspects and smoke cigarettes. When one cops asks the other why he should trust him, he replies, “Cause I’m the best.” The entire piece was done with a sarcastic sense of humor, but I would not at all be surprised if Mani drew most of his inspiration from To Live and Die in L.A.

Now I’ll be the first one to bitch about the abundance of reviewers, whether professional or amateur, deriding a film for its use of “cliches.” It seems no matter what the movie is or how it operates, everything has been seen or done before. Some people are just idiots and will cite 1984 ripped off The Matrix, when that would be anachronistically incorrect. Others will go on to say that Citizen Kane is the most cliched movie when it revolutionized the way films are made and stories are told. Films rely on certain filmic conventions. You cannot have a genre picture without drawing upon preceding sources. It is a way to anchor the audience to the story world by giving them a base of familiarity and expectations. Through this, the makers can proceed to add new elements to the genre. After all, one cannot expect a mass audience to accept a completely new and original film, if that were at all possible. That being said, To Live and Die in L.A. seems to do the bare minimum of a genre piece.

We have characters so stereotyped that they don’t even require a back story, a sadistic and artistically frustrated (!?) counterfeiter, shootouts with nameless bad guys, a murdered partner who “was two days away from retirement,” dirty urban arenas, double-crossers, bathed-in-blue night scenes, titty bars, tedious copulating, and an oh-so-wonderful soundtrack done by Wang Chung! Needless to say, Rhett still has not lost his 80s-boner.

We have characters so stereotyped that they don’t even require a back story, a sadistic and artistically frustrated (!?) counterfeiter, shootouts with nameless bad guys, a murdered partner who “was two days away from retirement,” dirty urban arenas, double-crossers, bathed-in-blue night scenes, titty bars, tedious copulating, and an oh-so-wonderful soundtrack done by Wang Chung! Needless to say, Rhett still has not lost his 80s-boner.

The seemingly only way To Live and Die in L.A. breaks away from generic conventions is in the way it deals with its characters. This film is completely without a heroic or likeable character. The closest it comes is with John Vukovich, who, I’m sorry, I cannot watch without seeing Paul Buckman’s cousin. The protagonists are so severely flawed that what is most interesting about watching them is the thrill of seeing them fuck up and make mistakes. One of the movie’s most memorable scenes is when Vukovich and Chance realize they are responsible for the death of a federal agent. It is actually refreshing to see a film handle characters in this way. This cause and effect world adds a greater sense of realism that is lacking from many movies.

Another interesting element is the female empowerment that seems to be present. There is an overbearing tone of homoeroticism in many scenes that stands in contrast to the hyper-masculinity and even misogyny of the male characters, Chance in particular. This machismo is also contested by the emasculating of many characters. A 9mm round finds its way into one gentleman’s crotch, and there are around a half dozen instances of groins being kicked. Add to this Masters’ main squeeze making off with another chick after his death and a deceptive female informant, and I believe we have a comment on how women are viewed in cop movies.

Another interesting element is the female empowerment that seems to be present. There is an overbearing tone of homoeroticism in many scenes that stands in contrast to the hyper-masculinity and even misogyny of the male characters, Chance in particular. This machismo is also contested by the emasculating of many characters. A 9mm round finds its way into one gentleman’s crotch, and there are around a half dozen instances of groins being kicked. Add to this Masters’ main squeeze making off with another chick after his death and a deceptive female informant, and I believe we have a comment on how women are viewed in cop movies.

Regardless of how this movie deals with these characters, there’s simply not enough here to demand any care or interest in this movie, outside of the shocking explicit bullet hits and a somewhat invigorating car chase. There is no close relationship between Chance and his murdered partner that you care to see his revenge carried out. It is implied, but it is not projected. William Petersen is so completely bland in his performance, and keeping his role on CSI in mind, I am beginning to think he is a fairly bad actor. The dialogue is often lame, but not outrageous enough to even consider this a fun, campy 80s film. There is an utter lack of visual style; everything is standard and pre-packaged.

If this film was so conscious of its genre, so much that is chose to make a comment on one element, it sold itself short by not going a few steps further. Perhaps we could have had a more self-reflective and interesting take on the cop genre.

I try to be as open-minded as possible when watching a movie, otherwise, why bother wasting your time? Every single film of William Friedkin’s that I have seen (The French Connection, The Exorcist, Cruising, Blue Chips, Jade, and The Guardian) I’ve found to be bloated bores, with a misunderstanding of how decadence and excess can be used to entertain the audience, rather than rubbing their nose in it. Somehow, he seemed to forget this tactic for To Live and Die in L.A., because he seems to embracing the slimy world he inhabits rather than criticizing it. Instead of pretending he isn’t dealing in cliches, he heads right towards them, and seemingly invents new ones. Most people give Lethal Weapon credit for re-invigorating the cop/buddy genre, but most of Lethal Weapon is taken right out of To Live and Die in L.A. which came out first, from the dialogue spoken by the about-to-retire cop, “I’m too old for this shit,” his out of control partner, who dabbles in cheating death, etc. But To Live is an altogether grittier film. Certainly Lethal Weapon wouldn’t have the balls to have the hero die in the end with a gruesome shotgun blast to the face.

Friedkin goes headfirst into everything 80’s in this film, ugly clothes and hair (check out Petersen’s partner Hart’s terrible rug), grating music, crude dialogue that makes one chuckle (“18th century Cameroon? Your taste is in your ass”) a completely un PC attitude towards women, completely gratuitous new wave art sequences, amongst many other things.

Friedkin goes headfirst into everything 80’s in this film, ugly clothes and hair (check out Petersen’s partner Hart’s terrible rug), grating music, crude dialogue that makes one chuckle (“18th century Cameroon? Your taste is in your ass”) a completely un PC attitude towards women, completely gratuitous new wave art sequences, amongst many other things.

In terms of gratuitous though, there is a lot of it in the nudity department, typical 80’s excess, strip clubs, etc., although I certainly wasn’t expecting a full frontal Petersen. But the naked Petersen gets at something that Friedkin chose to explore in atypical police procedural fashion, that being the constant homoeroticism between cop and criminal. When he introduces Dafoe by implying that he is kissing a man, it seems a throwback to Cruising, which this film also shares an ending with. Cruising had Al Pacino possibly switching his sexuality, and his girlfriend dressed in S&M garb, as a sort of ambiguous acceptance, which is extremely similar to the way that the previously freaked out John Pankow character, Vukovich, suddenly takes over Petersen’s role with his informant.

Dafoe’s sexual ambiguity (“Is this my package?”) is the perfect way for Friedkin to lead into his character’s ambiguity. Rick Masters fancies himself an unappreciated artist, having to deal with thugs and idiots on a regular basis, as a counterfeiter and painter, that’s why he burns his art, and why the beautiful scene where he makes all that money, is shot as if he really were creating something culturally important. In fact it’s the nicest looking scene in the whole film, as Freidkin fills the rest of the movie with burnt oranges, ugly purples, neon green, smokestacks, and car exhaust, as a contrast to the smooth and careful lighting when Masters creates the money. Masters almost seems to understand this, and that is why he is aware of his own fate within the film, and makes his own choices to head in that direction. He gives the cops options, such as setting up Pankow with the wonderfully sleazy lawyer played by Dean Stockwell, but never forces them to do anything. Masters knows he is being set up, never believes for a second that these guys are real businessmen, and goes forward with the deal anyway. Masters even sets up his own girlfriend with another girl, fully aware she will have to move on without him. He knows Chance is a Fed, he enjoys taking chances (going to see Turturro in prison, going to Maxwell’s house even though he knows the cops are watching, goes to where he knows Pankow will catch him, at the garage with the Chinese character). Friedkin is obviously less subtle here with the idea that there is little difference between cop and criminal, as he has named Petersen’s character Chance.

Dafoe’s sexual ambiguity (“Is this my package?”) is the perfect way for Friedkin to lead into his character’s ambiguity. Rick Masters fancies himself an unappreciated artist, having to deal with thugs and idiots on a regular basis, as a counterfeiter and painter, that’s why he burns his art, and why the beautiful scene where he makes all that money, is shot as if he really were creating something culturally important. In fact it’s the nicest looking scene in the whole film, as Freidkin fills the rest of the movie with burnt oranges, ugly purples, neon green, smokestacks, and car exhaust, as a contrast to the smooth and careful lighting when Masters creates the money. Masters almost seems to understand this, and that is why he is aware of his own fate within the film, and makes his own choices to head in that direction. He gives the cops options, such as setting up Pankow with the wonderfully sleazy lawyer played by Dean Stockwell, but never forces them to do anything. Masters knows he is being set up, never believes for a second that these guys are real businessmen, and goes forward with the deal anyway. Masters even sets up his own girlfriend with another girl, fully aware she will have to move on without him. He knows Chance is a Fed, he enjoys taking chances (going to see Turturro in prison, going to Maxwell’s house even though he knows the cops are watching, goes to where he knows Pankow will catch him, at the garage with the Chinese character). Friedkin is obviously less subtle here with the idea that there is little difference between cop and criminal, as he has named Petersen’s character Chance.

But Friedkin manages to get almost everything else right. This is a movie where cops make mistakes, Petersen and his partner fall asleep during a stakeout letting the guy be killed and their suspect get away. He even has a prisoner escape on him. There is a sense that they are human, and not just on auto-pilot, perfectly exemplified by John Pankow’s tendency to panic in the last half hour or so. There’s the hilarious portion of the car chase where Pankow is absolutely going out of his mind, at odds with the normal way that cops are portrayed as completely composed and confident at all times. And Pankow has what is probably the best moment of the film, as he points his gun at Dafoe in the garage, and he pauses, to have a moment of perspective and clarity, he can’t believe how far the whole thing has gone. Paul Thomas Anderson used a similar scene in Boogie Nights when Dirk realizes how badly his life has gone downhill, and he flips out within his own head, during a botched drug buy. For Pankow, like Diggler, the moment is when he switches over, when he realizes that self-sufficiency is what is important in most situations.

Those who criticize the film as dated seem to be missing the point. It firmly places itself in 1985, so it cannot be read any other way, hence the time specific basketball reference to Orlando Woolridge, the speech by Reagan in the opening scene (not unlike other cop movies that followed, this one also opens with a “shocking” action sequence that has nothing to do with the rest of the film), and the music. In fact, many would probably comment on Wang Chung’s immensely dated score. Certainly it was shrill and irritating. But I read it a different way. In the ugly world the movie presents, where there is no hiding from the evils of the world, I took it as if the music plastered in every scene, was like this irritating radio station that only played bad synth pop, and always in the character’s heads.

Those who criticize the film as dated seem to be missing the point. It firmly places itself in 1985, so it cannot be read any other way, hence the time specific basketball reference to Orlando Woolridge, the speech by Reagan in the opening scene (not unlike other cop movies that followed, this one also opens with a “shocking” action sequence that has nothing to do with the rest of the film), and the music. In fact, many would probably comment on Wang Chung’s immensely dated score. Certainly it was shrill and irritating. But I read it a different way. In the ugly world the movie presents, where there is no hiding from the evils of the world, I took it as if the music plastered in every scene, was like this irritating radio station that only played bad synth pop, and always in the character’s heads.

There are issues to be had with the film, the time element that we keep being given is totally unnecessary, and has no bearing on the story, just an base attempt by Friedkin to ratchet up the tension. And if the guy they rob from was a really Fed also, why did he have $50,000, when the only reason they went with the heist in the first place was because the limit they could get approval for was $10,000? But this is all overcome by the surprising humor throughout, from the arrest in the airport bathroom (“I just came in to take a leak”), the traffic report after the car chase, to the scene where the informant asks Petersen, out of self-preservation, what he would do if she stopped giving him information (“I’d revoke your parole”), to anything that Turturro does.

There are issues to be had with the film, the time element that we keep being given is totally unnecessary, and has no bearing on the story, just an base attempt by Friedkin to ratchet up the tension. And if the guy they rob from was a really Fed also, why did he have $50,000, when the only reason they went with the heist in the first place was because the limit they could get approval for was $10,000? But this is all overcome by the surprising humor throughout, from the arrest in the airport bathroom (“I just came in to take a leak”), the traffic report after the car chase, to the scene where the informant asks Petersen, out of self-preservation, what he would do if she stopped giving him information (“I’d revoke your parole”), to anything that Turturro does.

Hell, the only thing that could have made the movie better, was if the midget in a wheelchair who gives Petersen some information, had her own kung fu sequence.

Adam: So, Josh, start with your comment about the colors

Josh: Offensive

Adam: How so? You do realize the movie was made in the 80’s?

Josh: I feel as though I was anally raped by the 80’s

Adam: It firmly places itself in 1985 with the Reagan speech and the basketball references.

Rhett: And Wang Chung’s tunes

Josh: Yeah, Rhett, I referenced you in my thing, and your 80s boner, which I’m sure was turgid for about 6 days.

Rhett: A mention of the 80’s alone often gives me an erection.

Adam: It brings you to the time. It’s not dated if it brings you to the era it takes place in.

Josh: Adam, it does… but the 80s was a mixed bag. There’s good 80’s and bad 80’s.

Adam: This was great 80’s, the music was the best part. Because, yes it is annoying, but it’s like this horrid synth-pop noise playing in the character’s heads. Friedkin portrayed an ugly world, and this is just part of it. The color scheme is ugly, burnt orange, smokestacks, etc. The only pretty thing in the whole film is the counterfeiting sequence, because Masters sees himself an artist. That’s why he burns everything. His work is too good for the rest of the world, having to deal with thugs who don’t pay up.

Josh: Return of the Living Dead was good 80s, it brought you into the decade.

Rhett: a question I had going in was whether or not a movie could use the music from its time to poke fun at itself. Like in Scarface, the disco music was totally commenting on the hedonistic excess of their lifestyles. I thought that might be the case in LA, but the film seems to embrace the Chung music, and it uses it well.

Josh: yeah but when you’re in an era you don’t realize how ridiculous it is

Rhett: How about Dafoe burns his paintings because he does not care for the fame and glory? He does it as a form of artistic release, not for mere popularity.

Josh: Which is interesting because he himself burns up at the end.

Rhett: Life imitating art?

Adam: one of the best things about the ending, and there are many, is how Dafoe sees himself. He knows he’s going down, he knows they are cops, and he goes into it anyway. He’s tired of playing the game. That’s why he sets his girl up with Daphne from Frasier. He’s expecting to be killed.

Rhett: He very much has a destructive personality, just like his art…

Rhett: The one thing I didn’t like about the film was William Petersen’s penis. I think Harvey Keitel’s could have done a much better acting job.

Adam: I was surprised to see that. The movie is excessive in all the usual 80’s ways, but I didn’t see male full frontal coming, nor the homoeroticism.

Rhett: I love how he poked fun at the homoeroticism of his past films

Adam: I thought it was just sort of in tune with Cruising

Rhett: When Dafoe first kisses that performer…you are totally made to believe it is a guy, with the short hair.

Adam: Yes, exactly, and the scene with the “package” and “You’re beautiful.”

Rhett: I really think it is a brilliant film the way it comments and builds on Friedkin’s previous efforts. The ending is a nice twist on Cruising as well, with John morphing into Petersen, just like Pacino morphed into the gay murderer

Adam: That’s exactly how I read it. Sort of a better explained and appropriate version of Cruising‘s ending. It’s almost even the same last shot.

Rhett: The ending was one of the best I’ve seen in a long time, interesting on so many levels.

Adam: And I really dug how Friedkin went with his impulses and didn’t care about how offensive it might be to people, unlike all his other films.

Rhett: This seems to be his most personal work.

Josh: But at the same time there was nothing really cohesive about the film that really drew me in.

Adam: If you compare it to something similar that came out around the same time, like 8 Million Ways to Die, which was written by Oliver Stone, and Hal Ashby’s last film. That has a woozy, drugged out quality.

Rhett: Or Death Wish 3, that opened the same weekend.

Adam: To Live would never be made now, too un-PC.

Adam: To Live would never be made now, too un-PC.

Rhett: Definitely not, especially with the terrorist at the start. “I’m too old for this shit.”

Adam: And they would never let him have the ending either… People gave Lethal Weapon all that credit for that line and it’s all out of To Live.

Rhett: I don’t care if To Live invented it. It was cliché before it even existed.

Josh: Exactly. Thank you, Rhett.

Adam: Yeah, but it was actually quite appropriate in To Live, seeing as this guy does look haggard and he should have been dead with all that dynamite exploding behind him.

Rhett: That scene did not gel well with the rest of the film.

Josh: Yeah and he has only 3 days left… almost at retirement. Clichéd out the ass.

Adam: Rhett, it wasn’t supposed to gel. How many cop movies have some action scene that has nothing to do with the story opening the film?

Josh: I thought this was like The Manchurian Candidate at the start.

Rhett: I think Friedkin starts the film with endless clichés just so he can break the rules as the film goes on.

Josh: But he doesn’t break enough of them. The film itself did seem to be reflexive…. and conscious of its own genre… But at the same time it really suffered through uninteresting clichés.

Rhett: Well, I thought the film definitely upstaged the chase scene in The French Connection.

Josh: That chase scene started out lame and got better.

Rhett: The real showstopper was the counterfeiting scene. From that point on I was totally engulfed in the film.

Josh: I wasn’t at all. Though I thought the counterfeiting was cool and something that’s illegal and taboo, something the general public has no knowledge of how to do.

Adam: There is nothing like watching someone slowly do their job, step by step. Apparently, they really were doing it and they were concerned the FBI would bust in at anytime.

Rhett: Okay, how about the ever changing time cards. The font changed every time. Why?

Adam: That was one of the few things I disliked. It was a bald attempt by Friedkin to put more pressure on the characters but he didn’t use it at all. It was just there.

Josh: Yeah, Rhett, I noticed the font changes too and I also noticed they were totally arbitrary. They just signified nothing.

Rhett: It wasn’t the use of the time-cards, but the fact that the font changed for each one. Needlessly stylish.

Adam: There was another issue I had with the movie, if the guy they steal from is also an agent, how come he has more than $10,000, if that’s the limit?

Adam: There was another issue I had with the movie, if the guy they steal from is also an agent, how come he has more than $10,000, if that’s the limit?

Josh: I’m not sure…. but I thought that was a great twist, one of the few things that interested me.

Adam: Oh, it was a great twist, and I loved watching Pankow flip out.

Josh: Just call him Ira Buchman.

Adam: Especially during the chase, and when he’s in Dean Stockwell’s office.

Rhett: What I liked best about Petersen dying was that it was true to the character, yet a total departure for cop films.

Adam: yeah, he’s named Chance for a reason.

Rhett: With movies like Lethal Weapon and Bad Boys where the cops can do everything and live was a welcome change to show how vulnerable people can really be.

Adam: And To Live predated all the skydiving and base jumping movies.

Josh: Yeah, definite cause and effect.

Adam: But I thought that made it interesting, since Dafoe takes chances all the time as well, going to see Turturro in prison, going into that guy’s house when he knows the cops are watching. Friedkin went with the cop is just like the criminal idea which wasn’t really overly exploited until a few years later in The Killer.

Rhett: Dafoe seems to have a hint of homoeroticism laced within his character throughout such as when he kills that guy at his house, he refers to his ass. Then he refers to a pig ass and various other asses later and stays in a face to face with Petersen for several seconds. I liked how the counterfeiting was compared to his paintings. Like how he burns the bills just like he burns his paintings. Counterfeiting is an art to him.

Adam: Totally agree, that’s why he has the death wish, and why the counterfeit scene looks so much better than the rest of the movie.

Rhett: One weird thing was how Wang Chung’s music was plastered all over the soundtrack, yet there was not a peep of it during the car chase. But after that scene, you hear the radio announcing that there is a “slight” accident on the road, so you think having the radio would invite music too.

Adam: Because the characters were concentrating. Like they were in the moment, remember all the tension, Pankow is freaked out, and Petersen is filled with adrenaline.

Josh: ‘Cause obviously Wang Chung is not high tension. That mess was like a Blues Brothers accident.

Adam: But since the music was a self-reflexive comment on the era.

Josh: You’re guessing it’s self-reflexive.

Rhett: How do you see it as self-reflexive? The music seemed to really fit, I thought. No terrible vocals to really date it.

Adam: As I said before, the music is in the character’s heads, like they have to put up with the hideous sets, the color schemes, the music. It’s a big comment on the era as well as well as being an endorsement of its excesses.

Rhett: I can see the excess in shit like “Push it to the limit” from Scarface… But this one seems much more understated.

Josh: Rhett, exactly… It’s like Friedkin picked and chose what he wanted to comment on, and let the rest be like everything else.

Adam: Josh, I think that was the idea. He had his cake and ate it too.

Rhett: I just think the music was a product of it’s and not a self-reflexive one like Scarface or A Clockwork Orange time.

Adam: It’s sort of what Last Action Hero was trying for, be a parody of loud dumb action movies, as well as being one.

Josh: And how many people claim LAH is a great film.

Adam: I don’t think LAH works because of the huge scale. It’s what kills it.

Rhett: LA is much more personal and much less commercial.

Adam: Well the violence is much too grisly to be commercial. Usually, being shot in the face is not used as a recurring motif.

Rhett: To Live and Manhunter really work well together. Both very similar.

Adam: Well since this is Friedkin’s version of Miami Vice, it would make sense that Mann cast Petersen as well. There’s even a very similar scene. After his partner is killed, Pankow goes to Petersen’s house to try to get his side so they can be partners. Manhunter opens at Petersen’s beach house too, where a cop tried to recruit him for a job.

Rhett: Yeah, I kept getting distracted by Pankow’s stubble. I kept wanting to yell out Crockett!!

Adam: Did anyone else notice the computer music during the airport chase (and an example of what the movie also gets right, cop constantly screwing up) when he gets up on the railing? Sounds like someone was using a dial-up modem. I loved that whole scene anyway. Especially in the bathroom, “I just came in to take a leak.”

Rhett: Some good humor laced throughout that film, a rarity for Friedkin.

Adam: As well as when she asks him what will happen if she stops informing for him.

Rhett: What do you make of Dafoe’s fetish of videotaping himself during sexual acts?

Rhett: What do you make of Dafoe’s fetish of videotaping himself during sexual acts?

Adam: Rhett, I thought that should have been more explored. Sort of touches on his vanity, as well as the performance art aspect, with that whole mime thing.

Rhett: Yeah, seemed kind of incomplete. It’s a shame because Dafoe’s character is really interesting.

Josh: What do you think Ira Buchman’s turning into Chance at the end means?

Adam: That life runs in a cycle. Masters realizes this. He knows he will be replaced by another counterfeiter. That’s why he accepts his death, and even encourages it

Rhett: Who is Ira?

Adam: Rhett, Ira is Pankow, or Vukovich.

Josh: I guess Rhett didn’t grow up with Mad About You.

Adam: Sensible of him.

Josh: Mad about moose maybe. You see, cause…. he’s from Canada.

Rhett: I read the Pankow ending as a way for him to mask his guilt. If he becomes Petersen he can suppress the sorrow of seeing his partner die, so he creates a surrogate existence for Chance.

Josh: Yeah but his relationship with Petersen was so melodramatic. There’s literally nothing between them for like the first 45 minutes…

Rhett: Pankow weeps when Petersen dies. And considering Pankow was so worried he would get busted before. It seems that he is being chance as a way to avoid coming to terms with the whole thing.

Adam: I think the key to the ending is the final burning scene. There’s that shot where Pankow is about to kill Dafoe and he realizes how fucked up everything has gotten. And he has a moment of clarity and that’s when he switches over, just like Dirk in Boogie Nights. Of course during the moment of clarity, Dafoe hits him over the head, because he delays in shooting him. There’s this pause, for no reason. And Pankow is clearly having a moment in his head, as he aims at Dafoe.

Rhett: I liked how Dafoe was the one to light himself on fire at the end rather than Pankow.

Adam: Yeah, it seemed rather appropriate.

Rhett: He destroys his greatest creation of all…himself.

Adam: I am curious about what Josh didn’t like, since he said it was so clichéd, but seemed to like most of the scenes we discussed.

Josh: Like I said… it really didn’t offer up much than clichés and a bit of commentary and some ultraviolence…which was most enjoyable.

Adam: The only thing that would have improved it for me, was with that midget in a wheelchair painter; I think if she had a kung fu scene, it would have been the best movie ever.

Rhett: Or if she had a bigger penis than Petersen.

Josh: Like I always say man.. Any movie with Tom Sizemore and/or Gunkata would be much better than without.

Adam: Or if they used her chair for the car chase.